The Eight Gates of the Kingdom

Year A – Ordinary Time – 4th Sunday

Matthew 5:1–12: Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

We have reached the first stage of our journey following Jesus. We shall make a long pause with the Lord on a mountain called the Mount of the Beatitudes. Here Jesus will address us in a long discourse that occupies three chapters of the Gospel according to Matthew (Mt 5–7). It is the first of the five great discourses of Jesus in Saint Matthew and certainly the most decisive. It is his programmatic discourse, in which Jesus presents the essence of the lifestyle of his disciple.

The Seven Mountains in the Gospel of Matthew

One might say that the evangelist Matthew has a fondness for mountains. The word “mountain” appears fourteen times in his Gospel. Seven mountains in particular mark the public life of Jesus: from the temptations after his Baptism to the apostolic mandate after his Resurrection. These are not “physical” mountains, but places with a “theological” significance. The mountain carries a strong symbolic value of closeness to God. It is therefore pointless to search for the Mount of the Beatitudes on a geographical map. In fact, Saint Luke places this discourse on a plain. These seven mountains, symbols of fullness, punctuate the Gospel of Matthew.

- The Mountain of the Temptations (Mt 4:1–11): the starting point of the mission;

- The Mountain of the Beatitudes (Mt 5:1–7:29): here Jesus proclaims the “new Torah”;

- The Mountain of Prayer (Mt 14:23): a place of intimacy with the Father and discernment of the mission;

- The Mountain of the Transfiguration (Mt 17:1–8): where Jesus is revealed as the Son and the definitive Word;

- The Mount of Olives (Mt 24–25; 26:30): the mountain of waiting and judgement, where Jesus delivers the eschatological discourse and faces the agony before the Passion;

- The Mountain of Calvary (Mt 27:33): apparently defeat, in reality the enthronement of the Messianic King;

- The Mountain of the Mission (Mt 28:16–20), a mountain in Galilee (unnamed): here the risen Jesus entrusts the disciples with the universal mission.

The seven mountains form a theological itinerary of the Christian vocation:

Temptation → Law → Prayer → Revelation → Waiting → Cross → Mission.

The Mountain of the Beatitudes

“Seeing the crowds, Jesus went up the mountain; and when he sat down, his disciples came to him.” The “ascent of the mountain” and the act of “sitting down” are solemn gestures of the Teacher who sits in the chair of authority. This is a reference to Moses on Mount Sinai. Thus, this “mountain” is the new Sinai, from which the new Moses promulgates the new Law. The Law of Moses, with its prohibitions, established the limits not to be crossed in order to remain within God’s Covenant. The new Law, by contrast, opens up the horizons of a new project of life.

“He began to speak and taught them, saying: ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.’” Jesus’ discourse opens with the eight Beatitudes (the ninth, addressed to the disciples, is a development of the eighth). They are the prologue of Jesus’ discourse and the summary of the Gospel. It is a very well-known text, but precisely for this reason we risk skimming over it too quickly and almost ignoring, beneath its apparent simplicity, its richness, depth, and complexity. It is no coincidence that Gandhi also affirmed that these are “the highest words of human thought”.

I would simply like to invite you to read, reread, meditate upon, and pray with this text. Nevertheless, I venture to share with you some reflections that may help us to approach it more closely.

The Beatitudes are NOT…

- The Beatitudes are not the dream of an idealised, unattainable world, an utopia for dreamers. For the Christian, they are a criterion for life: either we accept them or we shall not enter the Kingdom! They are not, however, a new moral law.

- The Beatitudes are not a praise of poverty, suffering, resignation, or passivity. Quite the opposite: they are a revolutionary discourse! For this very reason, they provoke the violent opposition of those who feel threatened in their power, wealth, and social status.

- The Beatitudes are not an opiate for the poor, the suffering, the oppressed, or the weak, because they would dull their awareness of the injustice of which they are victims, leading them to resignation—even though they have often been used in this way in the past. On the contrary, they are an adrenaline that urges the Christian to commit himself to the struggle for the elimination of the causes and roots of injustice!

- The Beatitudes are not a postponement of happiness to the future life, in the hereafter. They are a source of happiness already in this life. Indeed, the first and the eighth beatitudes, which frame the other six, have the verb in the present tense: “for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven”. The other six have the verb in the future tense. Nevertheless, this is a promise that makes happiness already present today. It is the guarantee that evil and injustice will not have the final word. The world is not, and will not be, in the hands of the rich and the powerful!

- The Beatitudes are not (only) personal. It is the Christian community, the Church, that must be poor, merciful, weep with those who weep, and hunger and thirst for righteousness… in order to bear witness to the Gospel!

The Beatitudes ARE…

- The Beatitudes are a cry of happiness, a Gospel addressed to all. “Blessed” (makarios in Greek) can be translated as happy, congratulations, well done, I congratulate you… But we must realise that this message stands in complete contradiction to the prevailing mindset of the world.

- The Beatitudes are… one single reality! The eight are variations on a single theme. Each one sheds light on the others. Generally, commentators consider the first to be fundamental: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven”. All the others are, in some way, different forms of poverty. Whenever the Bible seeks to renew the Covenant, it begins by restoring the rights of the poor and the excluded. We might ask, however: why is there no beatitude about love? In reality, they are all concrete expressions of love!

- The Beatitudes are a person: they are the mirror, the self-portrait of Christ. To understand them and grasp their nuances, one must look at Jesus and see how each of them is fulfilled in his person.

- The Beatitudes are the key to entry into the Kingdom of God for everyone: Christians and non-Christians, believers and non-believers. In this sense, the Beatitudes are not “Christian”. They define who will enter the Kingdom. This is what Matthew 25 tells us about the final judgement.

- The Beatitudes are eight gates of entry into the Kingdom. To gain access, we must pass through one of these gates and belong to one of the eight categories of the Beatitudes.

Conclusion: what is my beatitude? Which one do I feel particularly drawn to? Which do I sense to be my vocation, by temperament and by grace? That is my gate of entry into the Kingdom!

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj

Fr. Manuel João, comboni missionary

Sunday Reflection

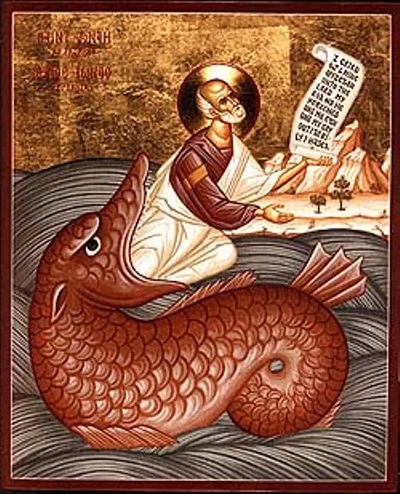

from the womb of my whale, ALS

Our cross is the pulpit of the Word