Christmas Within a Family

Year A – Christmas – Feast of the Holy Family

Matthew 2:13–15, 19–23: “Get up, take the child and his mother with you, and flee to Egypt”

The Feast of the Holy Family of Nazareth invites us to contemplate the mystery of Christmas in the context in which it took place, that is, within a family. The Gospels are very sparing in their details about the life of this family. This leads us to think that it was a completely ordinary life, without any particular events worthy of record. Only the Gospels of Matthew and Luke offer us a few references, with an intention that is more theological than historical. The apocryphal writings will later seek to fill this gap with imaginative stories, sometimes with creative references to the sacred text.

It is striking that the Feast of the Holy Family falls immediately after Christmas, when we are still immersed in lights, cribs and reassuring carols. Yet the Gospel that the Church places before us (Mt 2:13–23) is anything but gentle. It does not speak of domestic intimacy, family serenity or well-balanced lives. It speaks of fear, flight, night and exile. The Holy Family is not sheltered from drama: it is immersed in it up to the neck.

Perhaps this is precisely the first healthy jolt. We often live a sweetened version of Christmas, as if God had come to confirm our desire for a perfect, orderly and peaceful world. We dream of a family without conflict, a society without violence, a faith that shields us from wounds. But the Gospel quickly disillusions us: Jesus is born into a hostile world and does not magically fix it. He passes through it. And he will leave it imperfect, but not the same as before, because he sows within it something that was not there before: a new hope.

Matthew does not tell us a fairy tale for children. It is a “fairy tale for adults”, which unmasks our childish illusions. Christmas knows anguish. It is a pause of hope, not a consoling interlude. It is not the final destination of Advent, of waiting, but a stopping place to catch our breath and find courage, so as to live afterwards in the long, ordinary time of growth. That “in-between” time, between the old world and the one that is to come, is the space of our real life. It is there that faith is put to the test.

The family of Jesus must flee because power is afraid of life. And when power is afraid, it often kills. Above all, it kills the innocent and the defenceless. The Gospel does not soften this: Herod wants the child dead. And while the Magi return peacefully to their homes, Jesus loses his. For him, Christmas is a time of flight and forced journeys, of crossed borders and a suspended future. He is the God who becomes a refugee.

This is a strong word also for our families. Not because we must “do better” or “measure up” to an ideal model — that would be sterile moralism — but because the Gospel frees us from the illusion of the perfect family. Real families know fear, difficult decisions, nights without clear answers, limitations: they are imperfect. They know Egypt and Nazareth: places of temporary refuge, never definitive. And God is not scandalised by all this. He enters into it.

What also strikes us is the way salvation comes: through dreams. Something fragile and intangible. Joseph does not receive detailed plans, only essential instructions. “Get up. Take the child and his mother with you. Flee.” And he obeys, without extinguishing intelligence and responsibility. When Herod dies, the angel says, “You may return.” And Joseph reflects. He sees that in Judea, the region where Bethlehem is located, Archelaus reigns in place of Herod, just as violent. And he judges that it would be unwise to take the risk.

The ending of the passage, therefore, is anything but a “happy ending”. The Herods die, but their heirs remain. Evil does not disappear all at once. It changes its face, is passed on, reorganises itself. Joseph dreams, but he is not a naïve idealist. He knows how to read reality and recognise its dangers. He teaches us that hope is not the denial of evil, but the courage and shrewdness to pass through it. To dream, yes. But to act with prudence, without confusing faith with recklessness.

Perhaps this is the truest message of this feast. The Jubilee comes to an end, but hope does not. It remains renewed, more sober, less triumphalist. The Holy Family invites us to believe that even within precariousness, fear and imperfection something new can be born. It is not the perfect world we dream of, but the world of the “in-between”, in labour with hope.

And yet Jesus grows. In spite of everything. In a peripheral and unknown village, Nazareth, a symbol of a normality that is not heroic, not ideal and not perfect, but possible. This is what we are called to do: to discern concrete possibilities and to “inhabit” them. In our own “in-between” time.

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj

Fr. Manuel João, comboni missionary

Sunday Reflection

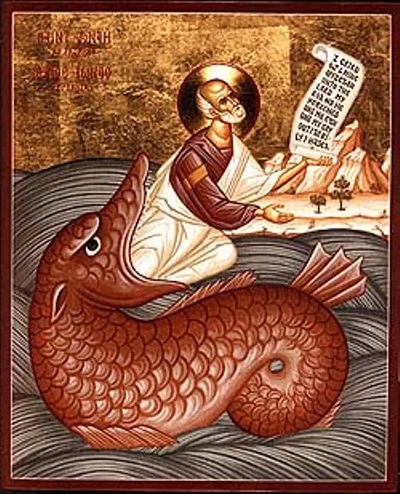

from the womb of my whale, ALS

Our cross is the pulpit of the Word