Healed… but not Saved!

Year C – Ordinary Time – 28th Sunday

Luke 17:11–19: “Stand up and go; your faith has saved you!”

At the time of Jesus, lepers embodied the figure of the utterly marginalised. Other skin conditions were also often generically labelled as “leprosy”. In the Mosaic Law (see Leviticus 13–14), it was considered a ritual impurity, not just a physical disease. The priest’s task was to verify the illness. The leper was declared “unclean” and had to live in isolation from the community. This isolation was not only sanitary but also religious and social: people believed leprosy was a sign of sin or divine punishment. They lived outside villages, often in groups or caves, surviving on charity or alms left for them from afar.

Healed but Not Saved

When the group cries out from a distance, “Jesus, Master, have pity on us!”, the lepers do not specify what they want from him — perhaps they are hoping only for an alms. But when Jesus tells them to go and show themselves to the priests, they understand that his intention is to heal them. It was the priests, in fact, who had the authority to certify a cure. So, trusting in Jesus’ word, they set out on their way.

Why then does Jesus, with evident sadness and disappointment — so clear in the triple question he asks — lament that only the Samaritan returns? Not because he expected a word of thanks! Rather, Jesus expected the miracle to be recognised as a messianic sign (cf. Mt 11:5 and Lk 7:22) — that is, to lead to conversion, as in the case of Naaman the Syrian in the first reading: “Now I know that there is no God in all the earth except in Israel” (2 Kings 5:15).

We might well ask: what wrong did the other nine do? They obeyed Jesus and were on their way to the priests. They would have “praised God” in the Temple with a sacrifice, celebrated with their families, and perhaps later come back to thank Jesus. So where did they go wrong?

In truth, only the Samaritan — the most excluded of the group, regarded as a heretic — is the one who, like the Samaritan woman at the well, recognises that the hour has come when neither on Mount Gerizim nor in Jerusalem will the Father be worshipped (Jn 4:21). Only the Samaritan “converts”. Jesus is the new Temple, the place where God is praised, the one who not only heals the body but saves the whole person in the depth of their being. The other nine are healed, but their journey of healing stops at the physical level. They remain bound to the old Temple and its cult. Only one is saved. He comes to faith and recognises Jesus as the Messiah. For this reason, Jesus says to him: “Stand up and go; your faith has saved you!”

This episode is like a parable reflecting our everyday reality. We all turn to Jesus seeking healing from our troubles, yet few choose the new path he opens. We prefer the familiar tracks — the ones that do not challenge us.

Some Reflections on the Gospel

1. Life and Faith on the Road

Today’s Gospel is full of movement: there are no fewer than ten verbs of motion in the passage. In a sense, it is an image of life itself, lived as a journey that stretches from birth to our passing from this world. Perhaps no other metaphor better expresses the course of human existence and history.

The life of faith is also a journey, beginning with baptism and proceeding — along diverse and often unpredictable paths — towards the heavenly goal. Everything in faith is lived and experienced “on the way”, step by step, with effort and perseverance.

The story can be read as an allegory of humanity and of Christian faith. There are ten lepers — a number symbolising completeness. All ten are healed, graced, yet only one is saved through faith. All share in God’s gifts, but few return to praise and depart transformed. Where gratitude is lacking, the gift is lost, as the theologian Bruno Forte writes.

2. A Journey of “Thank You”

Life and faith are first and foremost marked by gratuity: they are gifts. The unfolding of these gifts depends on the loving contribution of many hands. That is why “thank you” is one of the most frequent expressions in our daily speech. It is a spontaneous movement, though sometimes it can become mechanical. Saying thank you is not merely a matter of politeness but an attitude towards life. It means viewing existence not as “taking” but as “receiving”.

If this is true in ordinary life, it is even more so in the life of faith. The Greek text says that the Samaritan fell at Jesus’ feet “giving thanks” — eucharistōn. In this verb we find the word charis (grace), from which comes eucharistía. Saying “thank you” thus becomes thanksgiving — Eucharist.

In Scripture, thanksgiving accompanies every step of the believer: Jesus himself continually acts in thanksgiving to the Father. According to St Paul, the Church is called to be a people overflowing with gratitude. His letters abound in appeals to give thanks to God always, in everything and at all times: “Give thanks to God the Father at all times and for everything” (Eph 5:20).

3. A Life Without “Thank You” Becomes Ungraceful — and Disgraceful

A Jewish tradition says: “Whoever enjoys any good in this world without first saying a blessing or prayer of thanksgiving commits an injustice.” Ingratitude makes us dissatisfied, critical, complaining, pessimistic. We move from the logic of gift and welcome to that of greedy possession — claiming, demanding, mistrusting…

A life without “thank you” loses grace, and in time becomes disgraceful; finally, it turns into a kind of “hell” — the place, or rather the state, of one who does not recognise grace, becomes incapable of receiving the gift, and therefore refuses to give thanks.

4. “Where are the other nine?”

It is the same question Jesus puts to us. To us who, by grace, “are here”, returned to celebrate the “Eucharist”. I think of the crowds far from the Father of every gift (James 1:17), of our empty churches, our disoriented families… To receive this question is to have the courage and love to answer Jesus: “Here I am, Lord — I am here also on their behalf, to say to you: thank you!”

Cultivating Grace and Blessing

The ability to give thanks must be cultivated. Here is a simple exercise to strengthen it:

Each morning, enter the new day not through the outer door of busyness — of worries, problems to face, and pressures waiting for you — but through the inner door of the heart: the awareness of the gift of a new day, of gratitude and praise. This first step sets the pace for the day and determines its quality and colour — grey or radiant.

There are, in fact, two entirely different ways to begin and end each day’s journey: to enter the day blessed and to end it in thanksgiving, or to go through it ungrateful and ungraced.

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj

Fr. Manuel João, comboni missionary

Sunday Reflection

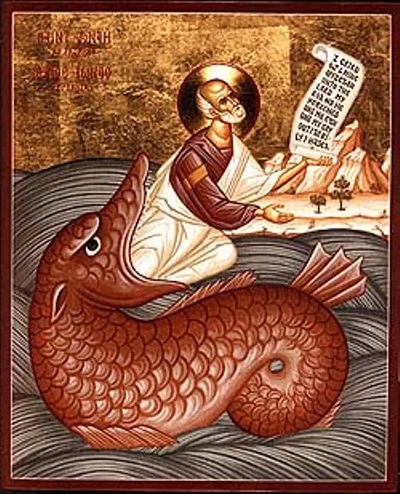

from the womb of my whale, ALS

Our cross is the pulpit of the Word