Fr. Manuel João, comboni missionary

Sunday Reflection

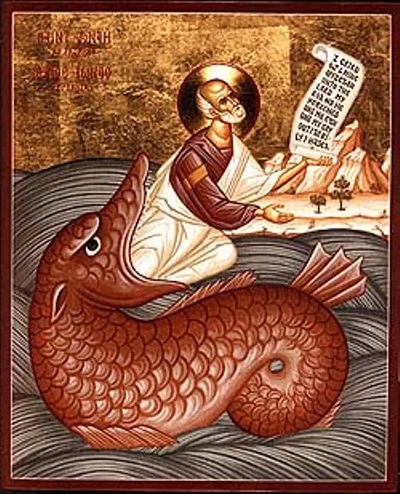

from the womb of my whale, ALS

Our cross is the pulpit of the Word

The Miracle of Prayer

Year C – 17th Sunday in Ordinary Time

Luke 11:1–13: “Lord, teach us to pray”

This Sunday’s Gospel offers us Luke’s version of the Our Father. We know by heart the version from the Gospel of Matthew, structured around seven petitions (Mt 6:9–13). Luke’s version is shorter, containing only five. However, this difference does not alter the essence.

“Jesus was praying in a certain place; and when he had finished, one of his disciples said to him, ‘Lord, teach us to pray.’” This anonymous disciple represents each one of us. Watching Jesus immersed in prayer stirs in us the desire to enter into his experience of deep intimacy with the Father—we who so often struggle to pray.

The Gospel passage is composed of three parts:

– Jesus’ prayer and the teaching of the Our Father (vv. 1–4);

– the parable of the persistent friend (vv. 5–8), encouraging us to pray without losing heart;

– and finally, the comparison with the relationship between father and child (vv. 9–13), to awaken in us the trust of a child:

“If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!”

God: Father or Step-Father?

Jesus speaks from his experience as Son. But why is ours often so different? Sometimes—unconsciously—we believe that the heavenly Father is harsher than our earthly one. Voltaire once wrote: “No one would want to have God as their earthly father,” and F. Engels added: “When a man knows a God more severe and cruel than his father, then he becomes an atheist” (quotes taken from Enzo Bianchi).

Where does this tragically distorted image of God come from? Perhaps from our disappointments in prayer? And might those not stem from a false understanding of prayer itself? In fact, many of our prayers are simply requests for… miracles! Asking for miracles is legitimate—but risky! Scripture considers that such prayer can amount to “putting God to the test” (cf. Lk 4:12), as it reduces God to an idol—and idols always disappoint!

True prayer is the highest expression of faith, hope, and charity. And when prayer is offered in trust, hope, and filial love, then indeed a miracle happens—not so much outside of us, but within—through the transforming action of the Holy Spirit.

Some reflections on the Our Father

Father, may your name be held holy, your kingdom come

“Father” is a name attributed to God in many religions. What is uniquely Christian is the awareness of being “children in the Son.” The nature of this prayer—spoken in the first person plural—is inherently missionary, since the “we” embraces not only the Christian community but all humanity.

We first ask the Father for the sanctification of his name—starting with ourselves: “You shall not profane my holy name” (Lev 22:32). Each of us can become a place where God’s name is continuously sanctified by revealing his fatherhood—or profaned.

The second petition is for the coming of God’s Kingdom. This was a deep yearning in Jesus’ time. In the New Testament, the expression “Kingdom of God” appears 122 times—90 of those on Jesus’ lips (F. Armellini). In Jesus’ preaching, Kingdom and Gospel seem to overlap (cf. Mk 1:15). The children of the Kingdom are the ferment of “a new heaven and a new earth where righteousness dwells” (2 Pet 3:13).

Give us each day our daily bread

The most humble request sits at the centre of the Our Father: the third of five in Luke, the fourth of seven in Matthew. Perhaps this is not by chance. It is in the sharing of bread that our sense of sonship and brotherhood is most clearly expressed.

In Jesus’ day, bread carried strong symbolic value: it was regarded as sacred. Breaking and sharing bread after the blessing of the head of the household was the highest gesture of family communion. Bread was broken by hand—gently—never cut with a knife.

Asking God for daily bread means acknowledging that everything comes from his fatherly hand. It implies a deep sense of fraternity: the Our Father is prayed in the plural, asking for bread not just for ourselves, but for all. It also evokes the call to simplicity, recalling the experience of the manna in the desert: it had to be gathered day by day, with no hoarding for the next day (Ex 16:19–21). Hoarding led to rot.

We live in a world where social inequalities have become dramatic and intolerable. Just days ago, a study by the NGO Oxfam revealed that four African billionaires hold more than half of the continent’s wealth. Today, we need prophetic voices like that of Saint John Chrysostom—and many other Church Fathers—who had the courage to cry out: “The rich man is either a thief or the heir of a thief!” This is why the request for “daily bread” is the most revolutionary and unsettling part of the Our Father.

Forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone who is indebted to us. And do not put us to the test.

The request for forgiveness is the most authentic way to place ourselves before God. We ask forgiveness for our sins: mine, ours, and those of all humanity. This request presumes in us a living awareness of sin—far from a given—and an honest and constant dialogue with God’s Word. We too are often like the Pharisees: skilled at “straining out a gnat and swallowing a camel” (Mt 23:24), ready to confess our “little sins” while closing our eyes to serious injustices we are, in one way or another, complicit in.

To the request for forgiveness is joined the plea about temptation. But what kind of temptation? The Greek word can also mean “trial.” Trial is a necessary part of the journey of faith: it can purify, but also endanger. That’s why we ask the Father to sustain us. There are exceptional trials, but also everyday ones, which are more subtle. Sometimes, monotony, daily fatigue, or simply the passing of time is enough to extinguish enthusiasm and cool our faith.

In the Our Father, temptation (or trial) appears in the singular. To understand its meaning, we can look to Jesus’ own experience. He undergoes two major trials: in the desert, where he must choose between following God’s word or giving in to the logic of the world; and in the Passion—especially at Gethsemane—where he confronts a face of God that seems shocking and mysterious, represented by the cross. These two trials, though distinct, are deeply united: both challenge his fidelity to the mission according to the logic of the Kingdom.

Thus, the trial—or temptation—spoken of in the Our Father is not simply the everyday temptations of life. It is the temptation of the disciple, of the missionary who has made the Kingdom his supreme desire and the sole reason for his life. (Bruno Maggioni)

For personal reflection

Meditate on and internalise this extraordinary and surprising declaration of Jesus:

“So I say to you: Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; those who seek find; and to those who knock, the door will be opened.”

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj