Fr. Manuel João, comboni missionary

Sunday Reflection

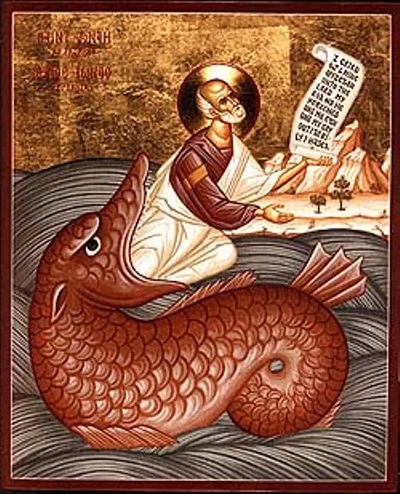

from the womb of my whale, ALS

Our cross is the pulpit of the Word

Becoming Neighbours!

Year C – 15th Sunday in Ordinary Time

Luke 10:25–37: “Who is my neighbour?”

This Sunday’s Gospel passage (Luke 10:25–37) recounts the parable of the so-called Good Samaritan. A doctor of the Law asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. Jesus invites him to answer the question himself, and the scribe gives a perfect summary of the Law: to love God and one’s neighbour. But when he then asks, “Who is my neighbour?”, Jesus replies with a parable.

A man, travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho, is attacked by robbers. The 27 km journey, with a drop of around a thousand metres (from Jerusalem at +750m to Jericho at -250m), was extremely dangerous as it passed through the rugged and arid wilderness of Judea – ideal for ambushes. For that reason, people usually travelled in caravans.

In the parable, Jesus presents the attitudes of three individuals towards the wounded man: a priest, a Levite, and a Samaritan. The priest and the Levite, both linked to Temple worship, see him and pass by on the other side. At this point, the listeners might have expected a third, “lay” character, with a hint of subtle anticlerical criticism – a critique that perhaps neither they nor we today would have objected to.

But Jesus introduces a Samaritan – a heretic, a foreigner, an enemy. Everyone is waiting to see what he will do. And what happens? The Samaritan, “on seeing him, was moved with compassion”. At this moment, I imagine everyone would have been stunned. The parable takes a prophetic turn, exposing empty and formal religiosity. Today, we might see ourselves reflected in the priest and the Levite: the “believers”, the practising. While the Samaritan represents those who, without appealing to God or His Law, act with generosity and altruism. In this sense, the parable deeply challenges us.

“What is written in the Law? How do you read it?”

The first reading (Deuteronomy 30:10–14), chosen to correspond with the Gospel, and the responsorial psalm (Psalm 19), speak of law, commands, precepts and statutes. They use verbs such as: to command, obey, observe, carry out… Concepts we struggle with today. Even though we understand that laws are necessary for social coexistence, we find it hard to accept limitations on our freedom. And when we discover that God’s Word governs even our relationship with Him, it can make us uneasy. With what sincerity have we repeated with the psalmist: “The precepts of the Lord rejoice the heart”?

We should then reflect on the counter-question Jesus poses to the doctor of the Law: “What is written in the Law? How do you read it?”. As if to say it’s not enough to know what’s written – one must also reflect on how that Word is understood. The “how do you read it?” is addressed to us, too. We must approach Scripture with the intention of moving from “what is written” to “how I understand and live it”.

It’s interesting to note that the first reading, the psalm, and the Gospel engage all of the human faculties: heart, soul, mind, eyes, hands… “You shall return to the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul”; “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbour as yourself”. If all of these dimensions are not involved, reading Scripture remains abstract, theoretical, partial, or even distorted.

Closeness and distance

The parable is born from the scribe’s question: “And who is my neighbour?”. It was a debated issue at the time. At best, a neighbour was only a fellow Jew who was practising. Jesus changes the perspective: to the question “Who is my neighbour?”, he effectively responds: “Don’t ask who deserves your love; be the one who becomes a neighbour to those in need”.

A key theme this Sunday is the concept of closeness. In the first reading we read: “This word is very near to you, it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you may carry it out”. The true sign that the Word is close is compassion, which makes us capable of approaching those in need, as the Samaritan does: “He came near him, saw him, and was moved with compassion”. And he drew close! This closeness is translated into concrete gestures: “He bandaged his wounds, pouring oil and wine on them; then he placed him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him”.

The Samaritan “was moved with compassion”. The verb used by Luke is splanchnizomai, which means to be deeply moved, “to feel it in the guts”. In Luke’s Gospel it appears only three times: when Jesus is moved before the widow of Nain (7:13), in our passage (10:33), and in the parable of the merciful father (15:20). In all three instances, compassion expresses itself in drawing near and touching. To be moved is a verb especially attributed to God. It’s no accident that the scribe doesn’t use this verb to describe the Samaritan, but instead the expression “show mercy”.

The conclusion of the parable is clear and direct: “Go and do likewise!” Become a neighbour. Show mercy. And you will become a son or daughter of the God of Compassion – like Jesus, the true “Good Samaritan”.

For personal reflection

“And now the truth emerges: there are people considered impure, not orthodox in faith, despised, who know how to ‘show mercy’, who know how to practise intelligent love for their neighbour. They do not appeal to the Law of God, to their faith, or to their tradition, but simply, as human beings, they know how to see and recognise the other in need and put themselves at the service of their wellbeing, care for them, and do what good is needed. This is mercy! In contrast, there are religious men and women who know the Law well and are zealous in observing it meticulously, who – precisely because they focus more on what is “written”, what is handed down, rather than on life itself, on what’s happening to them and on who is in front of them – fail to observe the true intention behind God giving the Law: which is love for others! But how can this be? How can it be that religious people, who go to church daily, pray and read the Bible, not only fail to do good, but even refuse to greet their brothers and sisters – something even pagans do? This is the mystery of iniquity at work within the Christian community itself! We shouldn’t be shocked, but we must examine ourselves, asking whether, at times, we too fall into the camp of those hardened ‘righteous’ ones – those legalists and pious people who do not see their neighbour but believe they see God; who do not love the brother they see but are convinced they love the God they do not see (cf. 1 John 4:20); those zealous activists for whom belonging to the community or the Church is a guarantee that blinds them, making them incapable of seeing the other in need.”

(Enzo Bianchi)

Fr. Manuel João Pereira Correia, mccj