GOOD FRIDAY

The Passion of the Lord

John 18:1—19:42

- First Reading: Is 52:13—53:12

- Second Reading: Heb 4:14–16; 5:7–9

- Gospel Reading: Jn 18:1—19, 19:42

Standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple there whom he loved he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son.” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother.” And from that hour the disciple took her into his home. After this, aware that everything was now finished, in order that the Scripture might be fulfilled, Jesus said, “I thirst.” There was a vessel filled with common wine. So they put a sponge soaked in wine on a sprig of hyssop and put it up to his mouth. When Jesus had taken the wine, he said, “It is finished.” And bowing his head, he handed over the spirit. (Jn 19:25-30).

Good Friday originated as the day of Jesus’s death (the 14th day of Nisan, which would have been Friday). It was a day of mourning accompanied by “fasting”, which was later extended to every Friday of the year.

The Liturgy consists of three moments: the Liturgy of the Word, the Adoration of the Holy Cross, and Holy Communion.

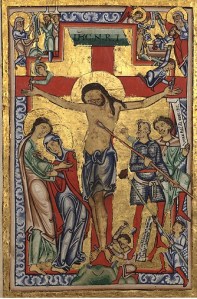

Today, through the Liturgy, the faithful are invited to fix their eyes on Jesus Crucified. He died on the cross to fulfill the mission of salvation the Father had entrusted to him: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world”. Isaiah says: “it was our infirmities that he bore, our sufferings that he endured, while we thought of him as stricken, as one smitten by God and afflicted” (Isaiah 52:13—53:12). With His life, Jesus paid the highest price for our disobedience, and He did it with and for love: Christ “became poor although he was rich, so that by his poverty you might become rich” (2 Cor 8:9).

Under the shadows of Good Friday, each one of us can place ourselves before the Cross and compare ourselves with the Lord Jesus regarding our own problems, our own tragedies, our own sufferings. Every one of life’s questions can be illuminated by the Cross to such an extent that we can truly say: “The heart has reasons that reason cannot understand.” The Lord Jesus deserves to be followed unto the end, just like He loved us.

Today’s Readings Are Full of Paradoxes

Who can believe this? Who will believe what we have seen and heard? No one, in their “right” mind, would understand it. A person who, through blows and injuries, has lost their human form. A God who submits in obedience to all suffering. A scandal for the Jews, madness for the Gentiles… yet the wisdom of God.

This wisdom of God is the only thing that truly saves us from the personal and global madness we fall into again and again. Only that Cross lifted high (like the serpent in the desert), gazed upon, holds the power to heal. Therefore, on Friday, there are no reasons or words to offer, only silence and contemplation. The act of venerating the wood of the Cross is profoundly meaningful; it conveys the truth contained in the sign. “We adore you, O Christ, and we bless you, for by your holy Cross, you have redeemed the world.”

Cármen Aguinaco

http://www.godgossip.org

“Judas Was Standing With Them”

Raniero Cantalamessa

In the divine-human history of the passion of Jesus, there are many minor stories about men and women who entered into the ray of its light or its shadow. The most tragic one is that of Judas Iscariot. It is one of the few events attested with equal emphasis by each of the four Gospels and the rest of the New Testament. The early Christian community reflected a great deal on this incident and we would be remiss to do otherwise. It has much to tell us.

Judas was chosen from the very beginning to be one of the Twelve. In inserting his name in the list of apostles, the gospel-writer Luke says, “Judas Iscariot, who became (egeneto) a traitor” (Lk 6:16). Judas was thus not born a traitor and was not a traitor at the time Jesus chose him; he became a traitor! We are before one of the darkest dramas of human freedom.

Why did he become a traitor? Not so long ago, when the thesis of a “revolutionary Jesus” was in fashion, people tried to ascribe idealistic motivations to Judas’ action. Someone saw in his name “Iscariot” a corruption of sicariot, meaning that he belonged to a group of extremist zealots who used a kind of dagger (sica) against the Romans; others thought that Judas was disappointed in the way that Jesus was putting forward his concept of “the kingdom of God” and wanted to force his hand to act against the pagans on the political level as well. This is the Judas of the famous musical Jesus Christ Superstar and of other recent films and novels—a Judas who resembles another famous traitor to his benefactor, Brutus, who killed Julius Caesar to save the Roman Republic!

These are reconstructions to be respected when they have some literary or artistic value, but they have no historical basis whatsoever. The Gospels—the only reliable sources that we have about Judas’ character—speak of a more down-to-earth motive: money. Judas was entrusted with the group’s common purse; on the occasion of Jesus’ anointing in Bethany, Judas had protested against the waste of the precious perfumed ointment that Mary poured on Jesus’ feet, not because he was interested in the poor but, as John notes, “because he was a thief, and as he had the money box he used to take what was put into it” (Jn 12:6). His proposal to the chief priests is explicit: “‘What will you give me if I deliver him to you?’ And they paid him thirty pieces of silver” (Mt 26:15).

But why are people surprised at this explanation, finding it too banal? Has it not always been this way in history and is still this way today? Mammon, money, is not just one idol among many: it is the idol par excellence, literally “a molten god” (see Ex 34:17). And we know why that is the case. Who is objectively, if not subjectively (in fact, not in intentions), the true enemy, the rival to God, in this world? Satan? But no one decides to serve Satan without a motive. Whoever does it does so because they believe they will obtain some kind of power or temporal benefit from him. Jesus tells us clearly who the other master, the anti-God, is: “No one can serve two masters… You cannot serve God and mammon” (Mt 6:24). Money is the “visible god”[1] in contrast to the true God who is invisible.

Mammon is the anti-God because it creates an alternative spiritual universe; it shifts the purpose of the theological virtues. Faith, hope, and charity are no longer placed in God but in money. A sinister inversion of all values occurs. Scripture says, “All things are possible to him who believes” (Mk 9:23), but the world says, “All things are possible to him who has money.” And on a certain level, all the facts seem to bear that out.

“The love of money,” Scripture says, “is the root of all evil” (1 Tim 6:10). Behind every evil in our society is money, or at least money is also included there. It is the Molech we recall from the Bible to whom young boys and girls were sacrificed (see Jer 32:35) or the Aztec god for whom the daily sacrifice of a certain number of human hearts was required. What lies behind the drug enterprise that destroys so many human lives, behind the phenomenon of the mafia, behind political corruption, behind the manufacturing and sale of weapons, and even behind—what a horrible thing to mention—the sale of human organs removed from children? And the financial crisis that the world has gone through and that this country is still going through, is it not in large part due to the “cursed hunger for gold,” the auri sacra fames,[2] on the part of some people? Judas began with taking money out of the common purse. Does this say anything to certain administrators of public funds?

But apart from these criminal ways of acquiring money, is it not also a scandal that some people earn salaries and collect pensions that are sometimes 100 times higher than those of the people who work for them and that they raise their voices to object when a proposal is put forward to reduce their salary for the sake of greater social justice?

In the 1970s and 1980s in Italy, in order to explain unexpected political reversals, hidden exercises of power, terrorism, and all kinds of mysteries that were troubling civilian life, people began to point to the quasi-mythical idea of the existence of “a big Old Man,” a shrewd and powerful figure who was pulling all the strings behind the curtain for goals known only to himself. This powerful “Old Man” really exists and is not a myth; his name is Money!

Like all idols, money is deceitful and lying: it promises security and instead takes it away; it promises freedom and instead destroys it. St. Francis of Assisi, with a severity that is untypical for him, describes the end of life of a person who has lived only to increase his “capital.” Death draws near, and the priest is summoned. He asks the dying man, “Do you want forgiveness for all your sins?” and he answers, “Yes.” The priest then asks, “Are you ready to make right the wrongs you did, restoring things you have defrauded others of?” The dying man responds, “I can’t.” “Why can’t you?” “Because I have already left everything in the hands of my relatives and friends.” And so he dies without repentance, and his body is barely cold when his relatives and friends say, “Damn him! He could have earned more money to leave us, but he didn’t.”[3]

How many times these days have we had to think back again to the cry Jesus addressed to the rich man in the parable who had stored up endless riches and thought he was secure for the rest of his life: “Fool! This night your soul is required of you; and the things you have prepared, whose will they be?” (Lk 12:20)!

Men placed in positions of responsibility who no longer knew in what bank or monetary paradise to hoard the proceeds of their corruption have found themselves on trial in court or in a prison cell just when they were about to say to themselves, “Have a good time now, my soul.” For whom did they do it? Was it worth it? Did they work for the good of their children and family, or their party, if that is really what they were seeking? Have they not instead ruined themselves and others?

The betrayal of Judas continues throughout history, and the one betrayed is always Jesus. Judas sold the head, while his imitators sell the body, because the poor are members of the body of Christ, whether they know it or not. “As you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me” (Mt 25:40). However, Judas’ betrayal does not continue only in the high-profile kinds of cases that I have mentioned. It would be comfortable for us to think so, but that is not the case. The homily that Father Primo Mazzolari gave on Holy Thursday 1958 about “Our Brother Judas” is still famous. “Let me,” he said to the few parishioners before him, “think about the Judas who is within me for a moment, about the Judas who perhaps is also within you.”

One can betray Jesus for other kinds of compensation than thirty pieces of silver. A man who betrays his wife, or a wife her husband, betrays Christ. The minister of God who is unfaithful to his state in life, or instead of feeding the sheep entrusted to him feeds himself, betrays Jesus. Whoever betrays their conscience betrays Jesus. Even I can betray him at this very moment—and it makes me tremble—if while preaching about Judas I am more concerned about the audience’s approval than about participating in the immense sorrow of the Savior. There was a mitigating circumstance in Judas’ case that I do not have. He did not know who Jesus was and considered him to be only “a righteous man”; he did not know, as we do, that he was the Son of God.

As Easter approaches every year, I have wanted to listen to Bach’s “Passion According to St. Matthew” again. It includes a detail that makes me flinch every time. At the announcement of Judas’ betrayal, all the apostles ask Jesus, “Is it I, Lord?” (“Herr, bin ich’s?”) Before having us hear Christ’s answer, the composer—erasing the distance between the event and its commemoration—inserts a chorale that begins this way: “It is I; I am the traitor! I need to make amends for my sins.” (“Ich bin’s, ich sollte büβen.”). Like all the chorales in this musical piece, it expresses the sentiments of the people who are listening. It is also an invitation for us to make a confession of our sin.

The Gospel describes Judas’ horrendous end: “When Judas, his betrayer, saw that he was condemned, he repented and brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and the elders, saying, ‘I have sinned in betraying innocent blood.’ They said, ‘What is that to us? See to it yourself.’ And throwing down the pieces of silver, he departed; and he went and hanged himself” (Mt 27:3-5). But let us not pass a hasty judgment here. Jesus never abandoned Judas, and no one knows, after he hung himself from a tree with a rope around his neck, where he ended up: in Satan’s hands or in God’s hands. Who can say what transpired in his soul during those final moments? “Friend” was the last word that Jesus addressed to him, and he could not have forgotten it, just as he could not have forgotten Jesus’ gaze.

It is true that in speaking to the Father about his disciples Jesus had said about Judas, “None of them is lost but the son of perdition” (Jn 17:12), but here, as in so many other instances, he is speaking from the perspective of time and not of eternity. The enormity of this betrayal is enough by itself alone, without needing to consider a failure that is eternal, to explain the other terrifying statement said about Judas: “It would have been better for that man if he had not been born” (Mk 14:21). The eternal destiny of a human being is an inviolable secret kept by God. The Church assures us that a man or a woman who is proclaimed a saint is experiencing eternal blessedness, but she does not herself know for certain that any particular person is in hell.

Dante Alighieri, who places Judas in the deepest part of hell in his Divine Comedy, tells of the last-minute conversion of Manfred, the son of Frederick II and the king of Sicily whom everyone at the time considered damned because he died as an excommunicated. Having been mortally wounded in battle, he confides to the poet that in the very last moment of his life, “…weeping, I gave my soul / to Him who grants forgiveness willingly” and he sends a message from Purgatory to earth that is still relevant for us:

Horrible was the nature of my sins, but boundless mercy stretches out its arms to any man who comes in search of it.[4]

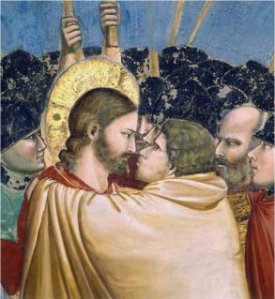

Here is what the story of our brother Judas should move us to do: to surrender ourselves to the one who freely forgives, to throw ourselves likewise into the outstretched arms of the Crucified One. The most important thing in the story of Judas is not his betrayal but Jesus’ response to it. He knew well what was growing in his disciple’s heart, but he does not expose it; he wants to give Judas the opportunity right up until the last minute to turn back, and is almost shielding him. He knows why Judas came to the garden of olives, but he does not refuse his cold kiss and even calls him “friend” (see Mt 26:50). He sought out Peter after his denial to give him forgiveness, so who knows how he might have sought out Judas at some point on his way to Calvary! When Jesus prays from the cross, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Lk 23:34), he certainly does not exclude Judas from those he prays for.

So what will we do? Who will we follow, Judas or Peter? Peter had remorse for what he did, but Judas was also remorseful to the point of crying out, “I have betrayed innocent blood!” and he gave back the thirty pieces of silver. Where is the difference then? Only in one thing: Peter had confidence in the mercy of Christ, and Judas did not! Judas’ greatest sin was not in having betrayed Christ but in having doubted his mercy.

If we have imitated Judas in his betrayal, some of us more and some less, let us not imitate him in his lack of confidence in forgiveness. There is a sacrament through which it is possible to have a sure experience of Christ’s mercy: the sacrament of reconciliation. How wonderful this sacrament is! It is sweet to experience Jesus as Teacher, as Lord, but even sweeter to experience him as Redeemer, as the one who draws you out of the abyss, like he drew Peter out of the sea, as the one who touches you and, like he did with the leper, says to you, “ I will; be clean” (Mt 8:3).

Confession allows us to experience about ourselves what the Church says of Adam’s sin on Easter night in the “Exultet”: “O happy fault that earned so great, so glorious a Redeemer!” Jesus knows how to take all our sins, once we have repented, and make them “happy faults,” faults that would no longer be remembered if it were not for the experience of mercy and divine tenderness that they occasioned.

I have a wish for myself and for all of you, Venerable Fathers, brothers, and sisters: on Easter morning, may we awaken and let the words of a great convert in modern times, Paul Claudel, resonate in our hearts:

My God, I have been revived, and I am with You again!

I was sleeping, stretched out like a dead man in the night.

You said, “Let there be light!” and I awoke the way a cry is shouted out!…

My Father, You who have given me life before the Dawn,

I place myself in Your Presence.

My heart is free and my mouth is cleansed; my body and spirit are fasting.

I have been absolved of all my sins, which I confessed one by one.

The wedding ring is on my finger and my face is washed.

I am like an innocent being in the grace that You have bestowed on me.[5]

This is what Christ’s Passover can do for us.

- [1] William Shakespeare, The Life of Timon of Athens, Act IV, sc. 3, l. 386.

- [2] Virgil, The Aeneid, 3.57.

- [3] See Francis of Assisi, “Letter to All the Faithful,” 12.

- [4] Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio 3.118-120: English trans. Mark Musa (Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 1985), 32.

- [5] Paul Claudel, Prière pour le dimanche matin [Prayer for a Sunday Morning], in Œuvres poétiques (Paris: Gallimard, 1967), 377.

Father Cantalamessa, in St. Peter’s Basilica, this Friday, April 18, 2014, during the celebration of the Passion presided by Pope Francis

WE CONTEMPLATED A LOVE STRONGER THAN DEATH

Fernando Armellini

All four evangelists devote two chapters to the story of the passion and death of Jesus. They refer to the same dramatic events and, although their versions of events are not identical and cannot be put together into one perfectly consistent story from the historical point of view, they essentially agree.

The differences come from the particular sensitivity of each evangelist, for which some episodes are narrated by one and ignored by others; some details left out by the Synoptics are instead developed by John.

The goal of the evangelists was not to keep a written record, report of events or chronicle of the facts identical in every detail, but to nourish the faith of the believers and to enlighten them about the significance of the events during Easter.

The absurd death of Jesus caught the disciples unprepared. It had aroused in them disturbing questions, the same ones we ask ourselves today: is it wise to trust a loser, who was betrayed and denied by his own friends? Does it make sense to take a man as a model that legitimate religious authorities have deemed a blasphemer, and that the Roman procurator sentenced to execution as a criminal? Do we admit that he was a persecuted just man, but then why didn’t God intervene to defend him?

With the passion narrative, John, more than giving us information on how the events took place, wants to help us understand the meaning of what had happened.

Before going into the details of the message that this evangelist intends to communicate, it is necessary to preface a reflection on the reasons why Jesus was executed. To those who have internalized some fairly superficial image of his person, his death can only be completely absurd. How can one who cures the sick, embraces and caresses the children, loves the poor and became a servant of all be killed?

Must his death then be attributed to a mysterious will of the Father who, in order to forgive man’s sin, needed to see the blood of the righteous? This kind of explanation cannot even be considered. Why, then, was Jesus crucified? In that sense, did he give his life for us? From which bondage has he delivered us by giving himself into the hands of men?

The reason for the hostility that has been unleashed against him is clearly indicated by John from the first page of his Gospel: Jesus was the light, “the light that shines in the darkness, light that darkness could not overcome” (Jn 1:4-5). “He was the true light that enlightens everyone” (Jn 1:9), “but people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil” (Jn 3:19).

Some rays of this light that illuminated the night of the world have been particularly intense and provocative. They have enlightened the hearts of the simple people showering them with joy and hope, but they annoyed those who preferred to act in darkness.

Four of these rays appeared particularly unbearable to the holders of religious and political power.

The first ray was the face of God shown by Jesus.

The spiritual leaders of Israel put aside the sweet images of God, husband and father, preached by the prophets, and had educated the people to believe in a legislative and strict judging God, ready to unleash reprisals and retaliation against those who transgress his commands. The God preached by Jesus is the Father and is good, just good. We turn to him with the simplicity and confidence of a child, because he reserves the same tenderness to whoever accepts his word and whoever rejects it (Mt 5:45). He feeds the birds of heaven and clothes the lilies of the field (Mt 6:25-31), counts the hairs of our head and knows our needs before asking him (Mt 6: 8).

No one, not even the worst sinner, may fear Him. He “so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him may not be lost but may have eternal life. God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world; instead, through him, the world is to be saved” (Jn 3:16-17).

Nothing is more subversive to the mentality of the scribes and Pharisees who have built a God in their own image, a God who does not want to have anything to do with tax collectors and sinners. For these spiritual leaders, Jesus is a fool and a heretic (Jn 8:48), a blasphemer to be stoned (Jn 8:59; 10:31,39), be taken away, at the earliest possible time, because he is a danger to the faith handed down by the fathers and leads the simple people astray.

A second new ray of light is projected on false religion.

There is a religious practice that is an expression of true faith and this communicates serenity and peace. There is a religion that is just a set of external practices, invented by people to nourish, perhaps unconsciously, the illusion of an authentic relationship with the Lord. This kind of religion tires and presses; it is an unbearable and insupportable yoke (Mt 11:28-30). It is a religion that reduces the relationship with God to a scrupulous observance of rituals and always ends up being reduced to a cult and hypocritical formalism.

Jesus does not challenge this form of religion. He does not denounce the abuse. But in the heart, he rejects it in the name of his union with God. On several occasions, he quotes Isaiah’s phrase that is particularly dear to him: “This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me. The worship they offer me is worthless, for what they teach are only human rules” (Mk 7:7).

He observes the Sabbath, but believes man is superior to the Sabbath.

The apex of this rejection is the dramatic expulsion of the temple’s merchants. John places it at the beginning of his Gospel (Jn 2:13-22), because it sums up the rejection of ritual practices that are not an expression of a life of love. The only acceptable worship to God is indeed that which is done “in spirit and truth.”

This second ray of light has annoyed those who preferred darkness to light. From simple refusal they graduated to hostility and finally took the decision to eliminate Jesus because he disturbed the orderly unfolding of their religious practices: “It is better to have one man die for the people”—Caiaphas, the high priest, who presided over the solemn liturgies the temple, exclaimed (Jn 11:50).

A third ray was projected on people.

What is the model of man, the ideal of a self-realized person in our society? In Jesus’ time, successful men were members of the Sanhedrin, the priests of the temple, the rabbis who loved “walking around in long robes and being greeted in the marketplace, and who like to occupy reserved seats in the synagogue and the first places at feasts” (Mk 12:38-39). Worthy of honor were Philip and Antipas, the two sons of Herod the Great, who lived in splendid palaces and were flattered by their subjects.

For Jesus to aim at this success and get it, is not a success, but a failure. One day he asks the Jews “As long as you seek praise from one another, instead of seeking the glory which comes from the only God, how can you believe?” (Jn 5:44).Jesus also expects to be “glorified” and prays: “Father, give me, in your presence, the same glory I had with you before the world began” (Jn 17:5).

But the glorious day that he expected is not the one in which, mounted a donkey, he receives applause upon his entry into the holy city, but that of Calvary. There, lifted up on the cross, he is finally able to show how far the immense love of the Father for man reaches. “Unless the grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies it produces much fruit. Those who love their life destroy it, and those who despise their life in this world keep it for everlasting life” (Jn 12:24-25).

It is the reversal of the values of this world. For Jesus, the model of man is not the one who wins, but loses; not who dominates, but who serves; not those who think of their own interests, but those who sacrifice themselves for others.

This third ray of light was also unacceptable to those who—with a touch of irony, Jesus observes—“they preferred the favorable opinion of people, rather than God’s approval” (Jn 12:43).

The fourth ray of light was projected on society.

We live in a competitive society. From childhood, we assimilate the belief that if we do not compete to emerge, we risk losing everything. The eminent one dominates others and draws more attention to self.

What ray of light does Jesus cast on a society based on these principles of life? One day he sits down, takes “a child and placed him in the middle and embracing him he said to the Twelve: ‘Whoever welcomes a child such as this in my name, welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me, welcomes not me but the One who sent me’” (Mk 9:36-37). In Jesus’ time, the children were the symbol of those who did not count, those who had no value and were totally dependent on others. They did not produce anything; they only consumed and needed everything to be provided for them.

In the new world, these people will go from the periphery to the center. They will be offered the place of honor. The community of Jesus “embraces” the poor and the “children” who need to be assisted in every way, but may impede the orderly lives of others. He “embraces” them not in the sense that he passively accepts their whims and encourages sloth, but because he wants to help them grow and strive to become adults, who can be self-sufficient, capable of planning and building their own lives.

If Jesus’ death was caused by the liberating light he introduced into the world, then—we wonder—could it have been avoided? Yes, of course. If he had moved away from Jerusalem, as he had done on other occasions (Jn 11:54; 7:1; Mt 12:15-16), if he had returned to Nazareth to work as a carpenter, leaving the world to continue as before, there is no doubt he would have been left in peace.

Jesus did not seek his death on the cross, but to avoid it, he would have had to turn off the light he had switched on and deny all his proposals. He would have had to have joined the ranks, adapted to the current mentality, resigned himself to the triumph of evil, and abandoned humankind forever to the hands of “the prince of this world.”

He was tempted to do that, and if he had agreed to the suggestion of the evil one, he would not have ended on the cross and would have been successful in the eyes of the world. He would have obtained those “kingdoms of this world” that, from the beginning, Satan had promised. But it would have been the failure of his mission.

What has been said until now helps us understand the theological message of the Gospel being proposed on this Good Friday.

John, in his Gospel, portrays a figure of Jesus quite different from that of the other evangelists. The difference is reflected in the accounts of the Passion.

There, we notice from the first scene the arrest in Gethsemane (Jn 18:1-11). The Synoptic Gospels present Jesus prostrated on the ground, seized by “fear and anguish,” “sorrowful unto death,” in need of his disciples’ moral support. He begged them to stay close, to watch and to pray with him. John does not stress any of these profoundly human emotions of Jesus. He does not speak of the agony, his inner struggle, the prayer addressed to the Father to spare him “the cup.” He presents Jesus resolute and aware of everything. He is not overwhelmed by events, but is able to guide them in a sovereign way. The soldiers were not the ones who captured him. He gives himself spontaneously, repeating, twice: “I am.” No one takes away his life, it is he who, serenely, comes forward and gives it (Jn 10:17-18).

In front of him, the evil ones who, as always, move and act in the dark of the night, retreat and fall (Jn 19:16). The scene must be read and understood in the light of the Scriptures. “I am” in the Bible introduces a manifestation of God. When the Lord comes, the forces of evil are driven into retreat. They panic and roll on the ground.

The passage is a Midrashic expression the evangelist uses to convey a precious theological message. He invites us to read of the capture of Jesus and the events of his passion in the light of the Psalms: “When the wicked rush at me to devour my flesh, it is my foes who stumble, my enemies fall” (Ps 9:4).

With this reference to the Scriptures John wants to inspire courage and hope in those who are involved in the dramatic conflict between the light of the sky and the night of the world, and fear of being overwhelmed by evil forces. He invites them not to lose heart because the kingdom of darkness has on its side the power of weapons, but they are no match against the light of Christ. Even if the ranks of the evil seem to triumph, actually they are in disarray, its warriors “are groping in darkness, without light and stagger like drunks” (Job 12:25).

The Synoptic Gospels relate that, after his capture, Jesus was brought into the house of the high priest, Caiaphas. There, during the night, they gathered the elders and scribes to finalize an indictment to be brought before the governor, Pontius Pilate. John gives a slightly different version of events. He says that the interrogation took place overnight in front of Annas, father-in-law of Caiaphas (Jn 18:12-24).

Why does he put this old and seemingly innocuous man in the story at all? Annas was the high priest for ten years—from 6 to 15 A.D.—but, even after he was deposed by the Roman prefect, he remained powerful. After him, the coveted and prestigious office continued to be kept in his family for another fifty years; four (maybe five) of his children, a son-in-law, and a nephew succeeded him as high priest.

It was the patriarch of the family who controlled all the “religious” activities of the temple. It was he who controlled and managed the offerings of the pilgrims, the profits of the money changers, the businesses in oxen, lambs and doves for sacrifice, and pocketed the money that circulated under the table for the awarding of contracts.

The expulsion of the vendors by Jesus was more than a sacrilegious provocation; it was an attack on the enormous economic interests of Annas’ family. He could not tolerate any longer that the son of a Galilean carpenter daring to accuse him of having reduced the temple of the Lord to a “den of thieves.”

Annas is the most sinister figure in the Gospels. It was he who headed all the plots of the trial against Jesus. This is why John presents him as the symbol of the forces of evil, as the personification of those who prefer darkness to light, those who are determined to perpetuate by any means, even with crime, their power based on intrigue, injustice and lies. Jesus confronts him without fear. When asked for a clarification of his doctrinal positions, he replies calmly: “Why then do you question me? Ask those who heard me, they know what I said” (Jn 18:21).

Annas is the supreme prototype of those who can commit violence without getting their hands dirty. He brought up his servants to understand, even without his orders, when and how they should intervene to put an end to any hint of rebellion against the master. It is one of these servants who slaps Jesus. The reaction of the Master is calm, but firm: “If I have spoken wrongly, point it out, but if I have spoken rightly why do you strike me?” (Jn 18:23).

Like other characters in the Gospel of John, this servant too has taken on a symbolic value. He represents those who, most often through ignorance or naivety, but often also in self-interest, take the side of the strongest. It is easy to be enslaved by those who can emerge and prevail —no matter how and by what means. We can be fascinated by those who succeed, but without realizing it, end up by surrendering to them our freedom through a willingness to do anything to get approval and gratitude.

John invites everyone to reflect on the personality of this servant, because to please the powerful of this world and convinced of defending religion, one could end up slapping Christ and denying his word.

In the passion narrative, John devotes ample space to the trial before Pilate—twice as much as Mark— (Jn 18:28–19:16).

Reading the passage, the insistence of the evangelist on the movements of the Roman procurator, his continual entry and exit from the praetorium, is surprising. This coming and going had a religious motivation—the Jews could not enter the house of a pagan because they would be contaminated—but John uses it to compose a scene in which the theme of the kingship of Jesus is introduced.

If we subdivide the text according to the movements of the governor, we are faced with seven clearly laid out scenes (Jn 18:29-32; 18:33-38a; 18:38b-40; 19:1-3; 19:4-7; 19:8-11; 19:12-16). In them, in addition to the protagonist—Jesus—many characters move—Pilate, the Jews, the soldiers, Barabbas—who are real, but that, in the evangelist’s intention, are also symbols of different ways of positioning in front of the kingship of Christ.

Pilate represents the kingship of this world, the opposite of Jesus. It is the image of one whose highest values are achievement and maintenance of power, not justice and truth. It is he who believes that everything must be sacrificed for the sake of power and thinks that even the innocent may be put to death if reasons of state require it.

The Jews are the icon of those believers that distort the kingship of Christ, adapting it to their own narrow criteria. They are observant of religious practices, but unable to give up the image of God they have in mind. At the foot of the cross, they became angry at the inscription of Pilate proclaiming the universal kingship of Jesus. They want to continue to believe in the God who overcomes by force, not by love; they do not accept a humiliated and defeated king.

The soldiers of the Praetorian Guard are poor men. They are more victims than perpetrators. Uprooted from their land, away from their families, often humiliated by their superiors, they have lost all human feeling and unleash their rage on those who are weaker than they are. They are the image of those who have been brought up to believe only in the powerful, to respect the winners and to mock the losers. They represent those who take, without questioning, the side of power and are also willing to obey unfair or unjust orders.

Barabbas—which means son of an unknown father—was the name given to the children of no one. He is a criminal, a true son of the “father—the evil one—who was a murderer from the beginning” of the world (Jn 8:44). He represents all the bandits of history, all those who committed violence and bloodshed. People have often considered them heroes and preferred them to the weak.

After observing the characters, we consider two significant indications of time that appear in the passage.

The first is located at the onset: It is dawn (Jn 18:28). The new day has dawned, the night on which the evangelist drew attention to Judas leaving the Upper Room has ended, “as soon as he had eaten the bread. It was night” (Jn 13: 30).

In the darkness of this night various characters made their moves: Judas who, with a detachment of soldiers equipped with lanterns, torches and weapons, went to the garden and handed Jesu over; Malchus, the servant whose ear Peter cut off; Annas and his son Caiaphas, puppets manipulated by the hands of the “Prince of Darkness” (Jn 12:35-36) and then Peter, who denied the Master. At last, the darkness of this night, in which the evil one has celebrated triumph, is dissolving and the light begins to prevail.

The second indication of time—it was around noon—is recognized in the climax of the process (Jn 19:14). The sun will shine on the world in all its splendor that Pilate proclaims: “Behold your King.”

We are thus introduced to the theme of the kingship of Jesus around which revolves all seven scenes. In the ancient Middle East, the task of the king was to ensure that his people enjoyed freedom and peace. The monarchical experience of Israel was, however, disastrous. For four and a half centuries, incapable and wicked rulers sat on the throne of Jerusalem. Moved with pity, the Lord announced, through the prophets, that one day he himself would come to rule his people. How? The way that God fulfills his promises is always surprising; it never corresponds to human expectation.

John has already mentioned the kingship of Jesus in the first part of his Gospel (Jn 1:49; 6:15; 12:13,15), now, in chapters 18–19, he mentions the word “king” 12 times.

The climax is reached in two scenes, the middle (Jn 19:1-3) and the end (Jn 19:12-16). In the first scene, we have a parody on kingship in this world. The soldiers amuse themselves by scornfully proclaiming Jesus king.

John, so restrained in telling of the sufferings of Jesus, gives emphasis instead to the elements that characterize the enthronement of an emperor: the crown (of thorns), the purple robe, the cheers. Jesus who reacted to the slap of Annas’ servant does not oppose this travesty. He accepts it, because it demolishes the image of a strong and triumphant Davidic messiah that people expected. He ridicules all ambition, delusions of grandeur, power frenzies, aspirations to honorary titles and bows of adulation, as well as the race for the first places. The true king is now in plain sight, the successful man according to God’s criteria: the one who gives his life for love.

The final scene (Jn 19:12-16) is introduced with great solemnity. Pilate leads Jesus out, makes him sit on an elevated stage and proclaims: “Here is your King.” No one can understand the scope of the event. Yet it is with these words that the representative of the kingdoms of this world, without realizing it, handed over power, and acknowledged Jesus as the new king.

For the Jews (we do not forget who they represent!) the proposal of the Roman procurator is so absurd that they take it as a provocation. They do not want this kind of kings; he disappoints all expectations and is an insult to common sense: “Away, away, crucify him!”—they shout.

According to human criteria, Jesus is a failure. In God’s plan, however, his defeat dispels the darkness that overshadowed the world and allowed the perpetuation of all forms of injustice and dehumanization.

Jesus is there, in silence. He does not add a word because he has already explained everything. He expects each one to speak, to make their own choice. We can bet on the kingship of this world or commit our lives with him in building the kingdom after God’s own heart.

The success or failure of life depends on this decision. In John, the description of the way towards the place of execution is brief: “Jesus, bearing his own cross went out of the city to what is called the Place of Skull” (Jn 19:17). That’s all. There are no women weeping for him or man from Cyrene helping him to carry the cross. It is he himself who decides to go to the place where he will manifest his “glory.”

In the story of the crucifixion (Jn 19:18-37), John introduces some scenes and some details ignored by the other evangelists.

The first is the inscription on the cross. It served to explain to the passersby the motive of his condemnation. While the Synoptics only give it a quick note, John puts on it a strong emphasis (Jn 19:19-22). He recalls that it was composed and placed by Pilate and it was written in Hebrew (the sacred language of Israel), Latin (the language of the rulers of the world) and Greek (the language spoken throughout the empire).

The representative of Emperor Tiberius solemnly and officially confirmed again the kingship of Jesus and the new way of being king. All the people had to know that a new royalty was being introduced in the world. The Jews (of yesterday and today) reject it, but it will continue to be proclaimed from the cross until the end of time. It is a final proposal, irrevocable, and cannot be changed.

Pilate was an inadvertent prophet.

After the installation of the new king on his throne of glory—the cross—what happens? Unlike the other evangelists, John does not record the insults hurled against Jesus by the passersby, the chief priests, the scribes and the elders. There is a reason: this scandalous king for the Jews and foolishness to Gentiles (1 Cor 1:23) can be accepted or rejected, but no one, until the end of time, will ever ignore or make fun of him.

The division of the garments (Jn 19:23-24) is also narrated in the Synoptics, but only John precisely states that they were divided into four parts; only he speaks of the drawing of lots for the tunic woven in one piece and explicitly cites the verse of the Psalm: “They divided my garments among them and cast lots for my raiment” (Ps 22:19).

Why so much importance accorded to a seemingly minor incident? The ancients attributed a symbolic value to the cloak. They believed that it was imbued or soaked with the spirit of the man who wore it. The cloak indicated the person himself, his work, way of posturing and relating to others. This is why, in the rite of baptism, the neophytes put off the old cloak and put on a new one. Jesus’ robes represent his person, his whole life given. The number four indicates the four cardinal points, that is, the whole world to which Jesus is delivered.

Now the theological message that John wants to convey becomes clear: the sacrifice of Christ has a universal value; it is shared with every person. Unlike the clothes, the robe is kept intact. Although announced to all people and handed over to those of different cultures, his Gospel—which is Jesus himself—will always remain intact; no one will ever make any addition or cut any part.

The third scene that takes place on Calvary (Jn 19:25-27) is that of the mother who, at the foot of the cross, is entrusted to the disciple whom Jesus loved. From the historical point of view, the episode presents serious difficulties. Mark reports that some women—and mentions them by name—stood at a distance, but neither he nor the other two synoptic writers recall that Mary and John were at the foot of the cross.

Apart from this, it seems that the Roman law forbade relatives to go close to the place of execution. It is really unlikely that Mary Magdalene and the other women have been so insensitive as to allow a mother to witness the horrendous torture of the son. If understood as a fact, the calm words of Jesus and the manner inwhich he addresses his mother are surprising. “Woman”— he calls her—as he did in Cana (Jn 2:4); but in Israel, no child has ever called his mother in this manner.

All these data direct us towards a different interpretation from the chronicle. John does not want to draw attention to the thoughtful gesture of Jesus who, concerned about the fate of Mary, would have entrusted her to the beloved disciple. Knowing the esteem enjoyed by this woman within the community of the disciples, it was to be expected that there was a competition to welcome her into their homes.

We are faced with a page of theology, composed and inspired by a significant fact: the presence, near the Calvary, of some of Jesus’ most loved persons. The mother is—for John—the symbol of Israel faithful to her God. In Hebrew, Israel is feminine that is why, in the Bible, the chosen people are imagined as a woman, a virgin, wife and mother. It is from this “woman,” from this Mother Israel, that the new people of the Messianic era was born.

Jesus first exhorts this woman-Israel to receive as son, as the legitimate heir of the messianic promises, every disciple who follows Him, the new king of the world, and hold them right up to Calvary, that is, up to the gift of life. Then he turns to the new community—represented by the beloved disciple—and invites her to consider herself the daughter of the Mother-Israel from whom she was born.

If this desire of the dying Jesus had been understood and accepted, how many misunderstandings and crimes would have been avoided!

The death of Jesus takes place—as John tells us—in a sweet and serene way (Jn 19:28-30). No cry, no earthquake, no darkening of the sun. From the cross, he is the enthroned king whose sovereignly determines his own destiny. He brings to fulfillment the mission that the Father has entrusted to him: the veil that prevented man from contemplating the face of God’s love has fallen forever.

Still, one piece is missing, one last fragment is needed to complete the mosaic. “To fulfill the Scripture, Jesus says: I am thirsty” (Jn 19:28). Only John records these words and considers them important. The biblical text referred to can only be Ps 42:3: “My soul thirsts for the living God.”

With this expression, the psalmist declared his ardent longing to encounter the Lord. John reads in a symbolic sense the real thirst of Jesus bleeding and now dying. The thirst alluded to is his burning desire to bestow upon humanity the living water of which he spoke to the Samaritan woman. Even there, and only there—it is well known—he was thirsty and asked for something to drink, that is, acceptance and willingness to receive his gift.

His desire now is going to be realized. “After receiving the vinegar, he says “It is accomplished!’ He bowed down his head, gave up the Spirit” (Jn 19:30).

Here it is the water that quenches the thirst of humanity, the water that is the source of true life and is poured out on all those who approach the crucifix.

After the death of Jesus, everything is concluded, the Spirit was given. We could pass on to the story of the burial. But John realizes that it is necessary to help the disciples understand the extraordinary event. He does this by recalling a fact in itself marginal and unimportant: a soldier drove his spear in the lifeless body of Jesus (Jn 19:31-37).

To this, the evangelist draws attention with an insistence that may appear excessive; three times he appeals to the reliability of his testimony: “The one who saw it, has testified to it, and his testimony is true; he knows he speaks the truth, so that you also might believe” (Jn 19:35).

In this episode, he, therefore, saw a deeper meaning. The first key to reading is offered by mentioning—at the beginning of the passage—the time when it happened: it was the day of Preparation. It was the time when, in the esplanade of the temple, the priests were sacrificing the Passover lambs. It is an open invitation from the evangelist to read the event in the light of the Exodus story.

It is on Calvary—John wants to tell us—that, on the day of Preparation, the true Paschal Lamb is sacrificed. Giving his own blood, Jesus saved all humankind from the exterminator angel, from the evil spirit that is rooted in man and causes death.

To highlight this message even more, the evangelist recalls another detail ignored by the other evangelists: to hasten the death of the two robbers crucified with Jesus, the soldiers break their legs while they leave intact those of Jesus, who was already dead. Here is a new reminder of the Paschal Lamb to which—according to the provisions of the Book of Exodus—no bone must be broken (Ex 12:46).

Finally, the most important detail: one of the soldiers with a spear, struck the side of Jesus and from the wound immediately blood and something like water came out.

The physiological fact in itself has little relevance but, for John, it becomes an extraordinary sign. Blood for a Semite is the symbol of life: pouring it to the last drop means giving one’s life. Through the wounded side from which comes the last drop of blood it is thus possible to see the heart of God, to see his boundless love: “Yes, God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him may not be lost but may have eternal life” (Jn 3:16).

What benefit does the world gain from this immense love? “Unless the grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it produces much fruit” (Jn 12:24)—Jesus had said. The fruit is the outpouring of the Spirit, symbolized by the gushing of water from the side of Christ. The living water promised to the Samaritan woman, flows from God’s heart. John solemnly concludes the sublime page of theology that he has dealt with: “They shall look on him whom they have pierced.” It is a biblical quote that refers to a mysterious prophecy pronounced towards the end of the fourth century B.C. and kept in the book of Zechariah (Zec 12:10). It speaks of a just and innocent man who was pierced; soon after, however, the Lord has awakened in the people, responsible for that crime, a sharp pain, a sincere repentance. All repented and looked towards him whom they had pierced. They broke out in a desperate cry, a cry similar to that of the parents who lost their only son, comparable to mourning for the death of a firstborn son (Zec 12:10-11).

Who is this man and why was he killed? The prophet certainly referred to a dramatic event that happened in his time. We know nothing else. What interests us is that John has recognized in this mysterious person the image of Jesus.

All people will look to Christ, executed and pierced on the cross, as their savior. The Crucifix will become the reference point for all their choices and will direct all their lives.

The account of the deposition of the body of Jesus in the tomb (Jn 19:38-42) substantially corresponds to that of the Synoptics; however, John recalls some precious details that other evangelists ignore. “Nicodemus, who had come to Jesus by night” joins Joseph of Arimathea. He comes with a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about a hundred pounds. The two take the body of Jesus and wrapped it in linen cloths with the aromatic oils.

These details are amazing. First of all, the profusion of perfumes amazes. It speaks of 32.7 liters of precious, extremely expensive essence. An excessive quantity: to anoint a dead body a thousandth part would be more than enough.

In addition, the spices used are not suitable for embalming. They are those used at a wedding feast to perfume the clothes (Ps 45:9) and the bedroom: “I have sprinkled my bed with myrrh, aloes, and cinnamon”—says the woman in the book of Proverbs (Pro 7:17).

John is not telling of the burial of a corpse (note that he does not mention even the closing of the tombstone), but the preparation of the thalamus in which the groom rests.

The most beautiful image used by the prophets to explain the love of God had been that of the wedding. The Lord—they said—is the faithful husband and Israel is the bride who, unfortunately, often prefers the love of idols than God.

In the Gospels, the bridegroom is Jesus. He is the Son of God who came from heaven to take back the wife who abandoned him. From the beginning of his Gospel, John has referred to him as the bridegroom (Jn 3:29-30).

On the cross, Jesus gave the greatest proof of his love. It is an immense love because “there is no greater love than this, to give one’s life” (Jn 15:13), a passionate love like the one mentioned in the Song of Songs: “for love is strong as death … no flood can extinguish love, nor river submerge it” (Song 8:6-7).

Now the groom who loved so much awaits the embrace of the bride, the new community, represented by the disciples Joseph and Nicodemus, who are at the foot of the cross. This community makes a gesture full of symbolism: she covers the body in bandages—the wedding dress that will envelop the body of the groom—all perfumes at its disposal, without skimping, as did Mary of Bethany (Jn 12:1-11). With eyes full of tears, she shows she has finally realized how much she was loved.

The reference to the garden, finally, recalls the burial of the king of Judah (cf. 2 K 21:18,26). During the trial, Jesus was proclaimed king, crowned, clad in the purple robe and enthroned on the cross. Now he is buried not just as a groom, but also as king.

READ: Romans crucify Jesus. As he goes to his death, he carries the cross himself. He controls everything. He does not need assistance. He speaks to his mother and the Beloved Disciple, and before he dies, he bows his head and hands over the spirit. Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea bury Jesus.

PRAY: The Church filled with the Spirit continues the mission of Jesus. Pray for church leaders, that they may recognize and act on their mission to holiness for themselves and others.

REFLECT: Why did Jesus have to die? Why is there no pain and suffering in this Gospel’s account of the Passion? Does the handing over of the Spirit indicate the birth of the Church in this Gospel? Did Nicodemus become a believer?

ACT: Jesus has already gained victory over the world: when you are in difficulty or in any situation that you cannot handle, reflect on your faith, in every decision you make. Follow the freedom of Jesus in taking up a task today that has been refused by other people.

Fernando Armellini

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com