Fr. Manuel João, comboni missionary

Sunday Reflection

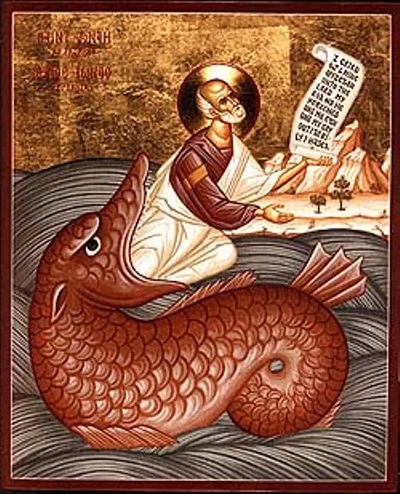

from the womb of my whale, ALS

Our cross is the pulpit of the Word

Misery and Mercy

Year C – Lent – 5th Sunday

John 8:1-11: “Go, and from now on do not sin any more!”

On our Lenten journey, the past Sundays have focused on proclaiming God’s mercy and calling us to conversion. Today, this path reaches its climax with the Gospel of the woman caught in the act of adultery.

This text (John 8:1-11) has had a troubled history: it is absent from the oldest manuscripts, ignored by the Latin Fathers until the 4th century, and never commented upon by the Greek Fathers of the first millennium. It’s like a page torn from its original context and inserted here into John’s Gospel. However, many scholars believe it may have originally belonged to St Luke, the evangelist of mercy.

This passage proved uncomfortable, as it clashed with the strict penitential discipline of the early centuries, when serious sins—murder, adultery, and apostasy—could only be forgiven once in a lifetime. Deep down, even today we struggle to move beyond the logic of justice and fully embrace the mindset of mercy.

What do you think?

The scene unfolds one morning in the Temple, where Jesus was teaching the people. The scribes and Pharisees bring him a woman caught in adultery, place her in the middle, and say to him:

“Master, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now, in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. What do you say?”

The evangelist notes that they said this to test him. The woman is just a pretext: the real target is Jesus himself—and his mercy. They want to see how he will handle this situation. If he hesitates to apply the Law, they can accuse him before the Sanhedrin; but if he calls for her condemnation, he will lose the favour of the people, who see him as a kind and compassionate teacher.

The practice of executing adulterers was common in the ancient Near East—a barbaric custom which, sadly, still exists today in some Islamic countries. It is also found in Leviticus 20:10: “If a man commits adultery with another man’s wife—both the adulterer and the adulteress are to be put to death” (cf. Deut 22:22). It served as a deterrent, but in practice, it was not strictly applied in Jesus’ time. Notice, too, that only the woman is brought forward. Where is the adulterer? The Law is not being applied impartially.

Jesus, instead of replying, bends down and begins to write with his finger on the ground in silence. What does he write? The sins of her accusers, as St Jerome suggests? Many speculations have been made! But perhaps the explanation is far simpler: doodling on the ground may have been a way to gain time, reflect, prepare an answer—or even release the irritation provoked by their question.

We find the expression “writing with the finger” only three times in Scripture. The first is in Exodus 31:18: the finger of God writes the Law on the stone tablets; the second, in the parallel passage of Deuteronomy 9:10; and the third, in Daniel 5, when a finger writes three words on the wall of the banquet hall where King Belshazzar is desecrating the sacred vessels taken from the Temple of Jerusalem.

What does Jesus write? The new law of love and mercy—written in the dust from which we were made, upon the fragility of our flesh, within our lives marked by unfaithfulness and sin. It is the new law God promised to write on the heart of every believer (Jeremiah 31:31-34).

Let the one who is without sin throw the first stone!

Jesus kept silent. But as they continued to question him, he straightened up and said: “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” Then, stooping down again, he wrote on the ground.

Jesus does not deny the Law, but he calls them to apply it first to themselves. All await someone “without sin” to cast the first stone. But none does. One by one, they leave. They had arrived together, full of confidence; now they leave, confused, slipping away in silence—starting with the elders. The stones are left on the ground. So too are the masks of those who had set themselves up as judges.

The woman’s accusers are forced to look within themselves, to confront the Law of Moses in their own lives. And they find themselves in her place. When we truly look inside ourselves, we can no longer condemn anyone. Often, unconsciously, when we fail to overcome the evil within us, we try to fight it outside—in others—and thus feel justified. This is when the mob mentality takes over: it only takes one person to throw the first stone, and the rest will follow. In this way, no one takes responsibility for the violence committed. If we do not fight the evil within, the enemy will always be someone else—someone to eliminate.

Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?

All have gone. Whether defeated or convinced, we do not know. And the woman remained there, alone, in the centre. On one side, misery; on the other, mercy, as St Augustine comments. Then Jesus stood up again, looked at her, and asked: “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” And she replied, “No one, Lord.”

Jesus “stood up” to look at her. According to the literal sense of the Greek verb, he “straightened himself up,” not “stood up.” He remains seated, low down: he does not look down on us, but looks up from below—for he has come to take the lowest place.

Then, the two gazes meet: hers, ashamed, fearful, and sorrowful; his, pure, gentle, and compassionate. It is a different gaze—one she has never known.

“It is the gaze that saves,” says Simone Weil. The Christian is called to reflect this gaze each morning—to realise how deeply loved they are, and to purify their view of others and the world.

Jesus calls her “Woman,” just as he addresses his own Mother in John’s Gospel. In doing so, he restores her dignity. And she, the Woman, calls him “Lord”—the Lord who saved her life.

This woman represents all of us, “adulterers,” unfaithful to the Bridegroom. We, too, belong to the “adulterous and sinful generation” (Mark 8:38).

Go, and from now on do not sin any more!

Then Jesus said: “Neither do I condemn you!” For “God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.” (John 3:17).

“Go, and from now on do not sin any more!” You are free from your past. Life is once again placed in your hands. You can begin anew!

These same words are addressed to us this Lent. So often, our lives are entangled with the past: with our failures, regrets over missed opportunities, our sins… But the Lord says: “Do not remember the former things, nor consider the things of old. See, I am doing a new thing—now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?” (Isaiah 43:16-21 – First Reading).

So let us imitate St Paul: “Forgetting what lies behind and straining towards what lies ahead, I press on towards the goal.” (Philippians 3:8-14 – Second Reading).

Fr Manuel João Pereira Correia, MCCJ