3rd Sunday of Easter – Year B

Luke 24:35-48

The disciples told their story of what had happened on the road and how they had recognised Jesus at the breaking of bread.

They were still talking about all this when Jesus himself stood among them and said to them, ‘Peace be with you!’ In a state of alarm and fright, they thought they were seeing a ghost. But he said, ‘Why are you so agitated, and why are these doubts rising in your hearts? Look at my hands and feet; yes, it is I indeed. Touch me and see for yourselves; a ghost has no flesh and bones as you can see I have.’ And as he said this he showed them his hands and feet. Their joy was so great that they still could not believe it, and they stood there dumbfounded; so he said to them, ‘Have you anything here to eat?’ And they offered him a piece of grilled fish, which he took and ate before their eyes.

Then he told them, ‘This is what I meant when I said, while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses, in the Prophets and in the Psalms has to be fulfilled.’ He then opened their minds to understand the scriptures, and he said to them, ‘So you see how it is written that the Christ would suffer and on the third day rise from the dead, and that, in his name, repentance for the forgiveness of sins would be preached to all the nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses to this.’

WITH THE VICTIMS

According to the Gospel accounts, the Risen One presents himself with the wounds of the Crucified One. It’s not a trivial detail, of secondary interest, but an observation of important theological content. Without exception, the first Christian traditions insist on a fact which generally we aren’t used to value appropriately today: God hasn’t raised up just anyone; God has raised up someone who was crucified.

Said more concretely, God has raised up someone who has announced a Father who loves the poor and forgives sinners; someone who has given himself in solidarity with all victims; someone who, when he himself met with persecution and rejection, has maintained his total trust in God even to the end.

Jesus’ resurrection is, then, the resurrection of a victim. When God raised Jesus up, God doesn’t just free a dead man from the destruction of death. What’s more, God «does justice» to a victim of human beings. And this sheds new light on «God’s being».

In the resurrection God’s omnipotence doesn’t only manifest Self over the power of death. God is revealed to us also in the triumph of God’s justice over the injustices that human beings commit. Finally and in full manner, justice triumphs over injustice, the victim over the executioner.

This is the great news. God is revealed to us in Jesus Christ as the «God of the victims». The resurrection of Christ is God’s «reaction» to what human beings have done with God’s Son. Thus the first preaching of the disciples emphasizes: «You have put him to death by raising him on a cross…but God has raised him from among the dead». Where we put death and destruction, God puts life and freedom.

On the cross, God still kept silent. That silence isn’t a manifestation of God’s powerlessness to save the Crucified One. It’s an expression of God’s identification with the one who suffers. God is there sharing to the end the destiny of the victims. Those who suffer have to know that they aren’t plunged into solitude. God Self is in their suffering.

In the resurrection, on the contrary, God speaks and acts to set forth God’s creative power in favor of the Crucified One. God has the last word. And it’s a word of lifegiving love toward the victims. Those who suffer have to know that their suffering will end in resurrection.

The story continues on. There are many victims who suffer today, maltreated by life or unjustly crucified. The Christian knows that God is in that suffering. The Christian also knows God’s last word. That’s why our commitment is clear: defend the victims, struggle against all power that kills and dehumanizes; hope for the final victory of God’s justice.

José Antonio Pagola

http://www.gruposdejesus.com

The marks of the Crucified-Risen Lord and of Mission

Romeo Ballan mccj

The presence of Jesus, who accompanied the two disciples on their journey to Emmaus (Lc 24:13f), ended in discovering the identity of that mysterious traveller who had explained the Scripture to them, warmed their heart, broken the bread… “Then their eyes were opened and they recognized him, but he disappeared from their sight… They got up at once and went back to Jerusalem” (Lc 24:31-33). Today’s text of Luke begins at this point (Gospel), with the Eleven disciples and the Two of Emmaus who are exchanging their experiences regarding the Risen Lord’s apparitions (v. 34-35). Finally, at the end of that day – the first of the new calendar of human history! – Jesus himself appears to the whole group and says: “Peace be with you!” (v. 36).

The Easter experience of the disciples, who see and recognize the Risen Lord, becomes the proclamation, rather, the foundation itself of the mission of the apostles and of the Church of all time and of all places. Today’s text of Luke begins and ends with the same Easter message: the Two of Emmaus tell of their encounter with the Risen Lord and the Eleven are sent to preach to all nations repentance and the forgiveness of sins (v. 47).

The apostles were not naive believers; they took their time before accepting that Jesus was truly risen. Luke insists in saying that at first they were amazed, terrified, upset, filled with doubts, believing they were seeing a ghost (v. 37-38); then the Gospel begins to give concrete proofs of the corporeity of the Risen one. For his part, Jesus insists in saying: “It is I myself!” (v. 39) and gives palpable proof that it is He, the same Jesus “in flesh and bones”: he eats in their presence some cooked fish (v. 43), he invites them to look and touch his hands, feet and side (v. 39). Finally the disciples surrender themselves and believe: the wounds of the passion are now the visible and tangible marks that there is identity and continuity between the historical Christ and the risen Christ.

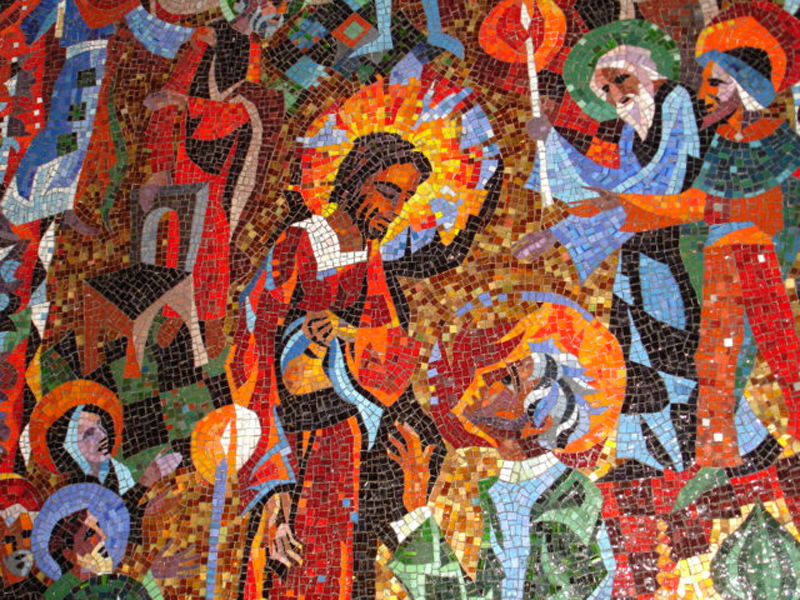

Normally, apart from special circumstances, people are recognized by their faces. Jesus instead asks his disciples – Thomas in particular – to recognize him by his hands, feet and side. “The attention is drawn to the wounds impressed by the nails and by the cross, the height of a life offered in love. Even after his resurrection the body of Jesus shows the marks of the total gift of himself… The Christian, too, will be recognized by his hands and feet… The witness of Christ’s resurrection is effective and credible only if the disciples, like their Master, are able to show to people their hands and their feet marked by works of love” (F. Armellini).

The three New Testament readings of this Easter Sunday have a common underlining purpose: repentance and the forgiveness of sins. Both – repentance and forgiveness – are rooted in the Easter mystery of Christ and are an essential part of the missionary proclamation of the Church. Peter (I Reading) declares so in the public square on the day of Pentecost: “Repent then and turn to God, so that he will forgive your sins” (v. 19). And John (II Reading) encourages by a loving expression (he says: “my children”) not to sin, but if anyone does sin, there is always a safety plank for us to hang on: “we have someone who pleads on our behalf… Jesus Christ, the righteous one… the victim of the sins of everyone” (v. 1-2).

This good news of salvation is given us as a gift of the Holy Spirit, who, for Luke as well as for John, is linked with the forgiveness of sins. Such a link is emphasized also by the new formula of sacramental absolution, as well as in a prayer of the Mass in which the Holy Spirit in invoked, because “He is the forgiver of our sins” (see the prayer on the offerings, on Saturday before Pentecost).

In John’s Gospel the institution of the sacrament of reconciliation for the forgiveness of sins happens on the day of Easter: “If you forgive people’s sins, they are forgiven” (Jn 20:23). The forgiveness of sins is, therefore, Jesus’ Easter gift. Rightly the great theologian and moralist Bernhard Häring calls the sacrament of reconciliation the sacrament of Easter joy. For Luke “repentance and forgiveness of sins”, then, are the good news the disciples will have to proclaim “to all nations”, in the name or, rather, on the mandate of Jesus (Lc 24:47). They are the signs of Jesus Crucified and Risen, the marks of his mission.

Gospel reflection

The experience of the Risen One told in this gospel passage took place in Jerusalem on Easter Sunday. The day began with the journey of the women to the tomb and with the announcement of the resurrection transmitted to them by “two men in dazzling garments appeared” (Lk 24:1-8).

At night, the eleven and a group of other disciples who were with them were talking of the manifestation of the Risen One that Simon and a few others had. Then the two disciples of Emmaus, almost out of breath, came and reported what had happened to them along the way and how they had recognized the Lord in the breaking of bread.

In this context, we can imagine the irrepressible joy when Jesus himself appeared among them (vv. 35-36).

We would expect the reaction John referred to us: “The disciples kept looking at the Lord and were full of joy” (Jn 20:20). Luke says instead that they were “amazed, frightened and upset,” believing of “seeing a ghost” and “doubts in their hearts” rose (vv. 36-38). Their reaction was inexplicable.

It is difficult then to understand the reason for their difficulty in believing: “In their joy they didn’t dare believe” (v. 41). How to reconcile joy with doubts? The fact that Jesus eat fish before disciples is also surprising (vv. 39-43). Paul ensures that the bodies of the resurrected is not material as what we have in this world (1 Cor 15:35-44); it is a “spiritual” body, passing through locked doors (Jn 20:26), therefore, cannot eat.

Some people think something similar happened as to what is told in the Book of Tobit, where it is said that the Archangel Raphael, the moment he makes himself known, said: “All the time that I was visible to you, I neither ate nor drank anything. I only appeared to do so” (Tob 12:19). But this explanation is not convincing, because, in this case, the “evidence” of corporeality given by Jesus would be based on an illusion, on a hallucination.

Jerusalem is sufficiently far away from the sea and it is very unlikely that the disciples could immediately pull out roasted fish. The fact would be more similar to Capernaum.

These difficulties, rightly highlighted by rationalists, are valuable. They lead us to go beyond the immediate meaning of the story in order to grasp the deeper meaning. Luke has resorted to a concrete language and material images to convey ineffable

truths. What do the wonder, fear, doubt, the fact of eating in front of the disciples mean and then… the strange recognition through the observation of the hands and feet? People recognize each other by face, not by the hands and feet.

Every experience of God told in the Bible is always accompanied by a reaction of fear on the part of man. We remember the exclamation of Isaiah at the time of his calling: “Poor me! I am doomed! For I am a man of unclean lips and yet I have seen the King, Yahweh Sabaoth” (Is 6:5). We think of Zechariah and Mary who were upset at the announcement of the birth of a child (Lk 1:12.29), or to the apostles who were filled with fear during the transfiguration (Mk 9:6).

This is not the terror that one experiences in the face of danger, but the amazement of those who receive a revelation from God.

In our passage too, the wonder and fear are biblical images. The evangelist uses it to describe a supernatural, ineffable experience of the disciples who were flooded by a light that is not of this world, but from God. They met the Risen One.

Wonder and fear always accompany even today, the manifestations of the Lord “in the middle” to his communities. Wonder and fear are the images of the radical changes that the apparition of the Risen Christ brings to human life. With its radiance, the light of Easter reveals the pettiness of each withdrawal to the current world and opens the minds and hearts on absolutely new reality to the world of the resurrected, world that fascinates and inspires wonder and fear, for it is God’s world.

To get involved in this new dimension is neither simple nor immediate. It includes hesitation and perplexity. There are doubts, as stressed, not only by today’s gospel (v. 38), but each story of the experience of the Risen Christ.

Skepticism, disbelief, uncertainty about the identity of the man who appeared have characterized the slow and arduous journey that led the apostles to the faith. To them, as to us, the reality of the resurrection has appeared, at times, too good to be true. In some circumstances, they had the feeling of having to deal with ghosts; other times, as happened on the Sea of Galilee, they have not recognized in the Risen One the Master whom they had followed along the roads of Palestine. Even after the last event on a mountain in Galilee—Matthew the Evangelist notes—“although some doubted” (Mt 28:17).

Their persisting doubts, even after so many signs offered by the Lord, prove that the apostles were not gullible; then they show that faith is not a surrender to the evidence, but it is the free response to a call. There are always good reasons to reject it, and the fact that there are non-believers proves that God acts in a very discreet way. He does not impose himself, does no violence to the freedom of the person.

Luke’s emphasis on the corporeality of the Risen One comes from a pastoral concern: the Christians he addressed to were imbued with the Greek philosophical ideas. They did not deny that, after death, he went into a new form of life, but this was reduced to survival of the spiritual component of man. The material body was considered to be a prison for the soul who sought to break away from the earth and to rise towards the sky. The bodily resurrection was inconceivable and, when apparitions of the dead were reported, they always imagined shadows, spirits, ghosts.

To let the newness of the Christian concept of the resurrection be understood by those who were linked to this culture, Luke—the only one among the evangelists—was forced to resort to a very “corporeal” language. The disciples—he assures—have touched the Risen One; they have eaten with him; they were invited to look at his flesh and his bones.

They are affirmations of a staggering realism. If one does not keep in mind who the recipients are and what is the objective which has led Luke to express himself in this way, one runs the risk of equating the resurrection of Jesus to the resuscitation of his cadaver, on his return to the way of life that he had before.

The resurrected ones do not take the material body, made up of atoms and molecules, which they had in this world. It would not make sense to be stripped at the time of death, of this body, and then get it back on the day of resurrection of the dead. God could not have decreed the death of a person in order to give him back the same form of life. If he destined the person to die it is to introduce him to a new way of life completely different from the present one, so different that it cannot be neither imagined nor verified. Our senses are not able to capture it; it can be grasped only through signs and be accepted in faith.

At this point we try to reformulate the passage’s theological message using a language more understandable to our culture.

The Risen One—ensures Luke—was not a ghost, but the same Jesus that the disciples had touched with their hands and with whom they had eaten. He had changed his appearance; a sublime metamorphosis that made him unrecognizable had taken place in him. He was transfigured, but it was not another person. He kept his body, his ability to manifest himself outwardly, to relate, to communicate his love, but his was a body different from ours, it was—as taught by Paul—a “spiritual” body (1 Cor 15:44).

He has a body that allows him to continue to eat and drink with us, that is, to share our hopes and delusions, our joys and sorrows. He is not out of reach, not a spirit irremediably distant and detached from our reality. Even after his return to the Father, he remains fully human, one of us.

He is not the only risen one; he is the first raised from the dead (Col 1:18). What happened to him is repeated in every disciple. At the time of death, there won’t be a split of the soul from the body (this is Greek philosophy, not a biblical concept), but the human, as a whole, will be transfigured in God’s world.

Now the invitation of the Risen Lord to look at his hands and his feet is better understood (v. 39). While people are identified by the face, Jesus wants to be recognized by the hands and feet. The reference is to the wounds impressed by the nails and to the cross, culmination of a life spent for love.

The body of Jesus conserves the signs of his total self-giving even as the Resurrected One.

God has no other hands but those of Christ, nailed for love. It would be blasphemous to imagine that they could do harm to the human. He has no other feet but that of Christ, nailed, and he showed them to tell us that he won’t be far away from us.

It is contemplating these hands and these feet that man discovers the true and only God.

The Christian will also be recognized by the hands and feet. Blessed are those who can show God their hands and their feet marked by acts of love. With Paul they can boast: “I bear in my body the marks of Jesus” (Gal 6:17).

In the last part of the passage (vv. 44-48) the way to make today the experience of the Risen Lord is shown: it is a must to open the hearts to the understanding of the scriptures. It is through the Scriptures that Christ continues to show to his disciples, “his hands and his feet,” that is, his gestures of love.

Then the big announcement also present in the other two readings is introduced: In the name of Christ conversion and the forgiveness of sins will be preached to all the nations.

To believe in the resurrection of the Lord involves a radical change of thinking and living. The night of the Passover marked, for the first Christians, the passage from death to life, through the sacrament of baptism (1 Jn 3:14).

The announcement of the resurrection of Christ is effective and credible only if the disciples can, like the Master, show people their hands and their feet marked by works of love.

by Fr. Fernando Armellini

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com