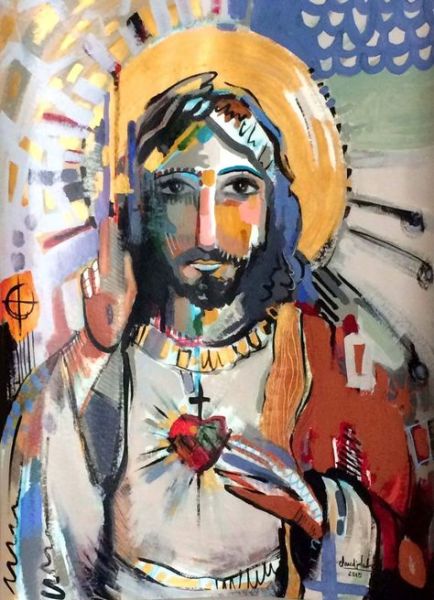

Feast of the Heart of Jesus

- First reading Deuteronomy 7:6-11

The Lord set his heart on you and chose you - Second reading 1 John 4:7-16

Let us love one another, since love comes from God - Gospel Matthew 11:25-30

You have hidden these things from the wise and revealed them to little children

Jesus exclaimed, ‘I bless you, Father, Lord of heaven and of earth, for hiding these things from the learned and the clever and revealing them to mere children. Yes, Father, for that is what it pleased you to do. Everything has been entrusted to me by my Father; and no one knows the Son except the Father, just as no one knows the Father except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.

‘Come to me, all you who labour and are overburdened, and I will give you rest. Shoulder my yoke and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. Yes, my yoke is easy and my burden light.’

God loves bonds, he creates bonds

Pope Francis

“The Lord set his love upon you and chose you” (Dt 7:7).

God is bound to us, he chose us, and this bond is for ever, not so much because we are faithful, but because the Lord is faithful and endures our faithlessness, our indolence, our lapses.

God was not afraid to bind himself. This may seem odd to us: at times we call God “the Absolute”, which literally means “free, independent, limitless”; but in reality our Father is always and only “absolute” in love: he made the Covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, with Jacob for love, and so forth. He loves bonds, he creates bonds; bonds that liberate, that do not restrict.

We repeated with the Psalm that “the love of the Lord is everlasting” (cf. Ps 103[102]:17). However, another Psalm states about we men and women: “the faithful have vanished from among the sons of men” (cf. Ps 12[11]:1). Today especially, faith is a value that is in crisis because we are always prompted to seek change, supposed innovation, negotiating the foundation of our existence, of our faith. Without faithfulness at its foundation, however, a society does not move forward, it can make great technical progress, but not a progress that is integral to all that is human and to all human beings.

God’s steadfast love for his people is manifest and wholly fulfilled in Jesus Christ, who, in order to honour God’s bond with his people, he made himself our slave, stripped himself of his glory and assumed the form of a servant. Out of love he did not surrender to our ingratitude, not even in the face of rejection. St Paul reminds us: “If we are faithless, he, Jesus, remains faithful for he cannot deny himself” (2 Tm 2:13). Jesus remains faithful, he never betrays us: even when we were wrong, He always waits for us to forgive us: He is the face of the merciful Father.

This love, this steadfastness of the Lord manifests the humility of His heart: Jesus did not come to conquer men like the kings and the powerful of this world, but He came to offer love with gentleness and humility. This is how He defined himself: “learn from me; for I am gentle and lowly in heart” (Mt 11:29). And the significance of the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which we are celebrating today, is to discover ever more and to let ourselves be enfolded by the humble faithfulness and the gentleness of Christ’s love, revelation of the Father’s mercy. We can experience and savour the tenderness of this love at every stage of life: in times of joy and of sadness, in times of good health and of frailty and those of sickness.

God’s faithfulness teaches us to accept life as a circumstance of his love and he allows us to witness this love to our brothers and sisters in humble and gentle service…

Dear brothers and sisters, in Christ we contemplate God’s faithfulness. Every act, every word of Jesus reveals the merciful and steadfast love of the Father. And so before him we ask ourselves: how is my love for my neighbour? Do I know how to be faithful? Or am I inconsistent, following my moods and impulses? Each of us can answer in our own mind. But above all we can say to the Lord: Lord Jesus, render my heart ever more like yours, full of love and faithfulness.

Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus 2014

Commentary on the Readings

First Reading: Deuteronomy 7:6-11

The emotion a woman feels, when the young man who is destined to become her husband, opening his own heart, for the first-time whispers: “I love you,” is memorable. Even Israel has never forgotten the day that his God has made the first declaration of love. The sacred author has kept in the moving page of Deuteronomy proposed to us today: “You are a people consecrated to the Lord” (v. 6).

It is the formula by which the Lord swore eternal love to Israel—his beloved—promising unswerving loyalty: “The Lord your God has chosen you from among all the people on the face of the earth, that you may be his own people” (v. 6).

Israel, the favorite. Why? All other nations ask. How is she able to draw to herself the attention and affection of the Lord? How did she conquer his heart? What’s so fascinating about her? Experience suggests us the answer: the lover’s heart is unpredictable; it follows its own logic; it has reasons that the mind does not understand.

One cannot command the heart. In fact, not even God was able to command his own heart. Logic required that—given its high position—he chose to ally himself with a famous people, powerful, worthy of him. Instead, he fell in love with Israel, not because it was the “most numerous among all the peoples,” but because it was the least, the most insignificant of all (vv. 7-8).

God is not attracted by the rich because they do not need anything; they have it all and no one can enrich them. His heart turns irresistibly to the poor because only to the poor he can deliver himself and give them all the best. Israel has this mission to carry out in the world: to remind always and to all what the Lord’s preferences are. It is the image of all those who will always recall the attention of God’s heart: the marginalized, the miserable, and the sinners, those who, in the eyes of the world, do not matter.

Paul understood it very well when he wrote to the Corinthians: “Yet God has chosen what the world considers foolish, to shame the wise; he has chosen what the world considers weak to shame the strong. God has chosen common and unimportant people, making use of what is nothing to nullify the things that are” (1 Cor 1:27-28).

In Jesus, God’s heart is made visible and showed his preferences for the last: he is born in a cave of the shepherds, grew up among the poor of the world, has chosen the company of tax collectors and sinners and returned to heaven bringing with him a criminal who represents the whole of humanity at last conquered by his love.

In the second part of the reading (vv. 9-11), God reveals to Israel—the bride he has chosen—what is expected of her: an answer without compromises or reservations to his immense love. If she refuses him she would decree her own ruin; she would declare her preference for her own misery than the condition of the queen.

The dramatic nature of this choice is presented in our passage—as in many other pages of the Bible—with the image of punishment, of retribution from God, the unrequited love (v. 10). It is a literary language that wants to draw attention to the responsibility assumed by one who rejects the proposal of the Lord.

According to people’s criteria, the spontaneous response to ingratitude is punishment. But God does not behave in this way because he cannot help but love, as assured by the prophet Hosea: “My heart is troubled within me and I am moved with compassion I will not give vent to my great anger … for I am God and not human” (Hos 11:8-9).

Second Reading: 1 John 4:7-16

More than the other evangelists, John gained insight into the secrets of the heart of Jesus and discovered the immensity of God’s love. He exclaimed with overwhelming joy: “See what singular love the Father has for us: we are called children of God and we really are” (1 Jn 3:1). In today’s passage, he takes up and develops the theme of divine sonship that filled him with wonder. He begins with an exhortation: “My dear friends, let us love one another for love comes from God. Everyone who loves is born of God and knows God” (v. 7).

Jesus made the same request to the disciples and presenting it as a commandment, as the hallmark of his followers: “Now I give you a new commandment: Love one another! Just as I have loved you, you also must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples if you have love for one another” (Jn 13:34-35).

John does not speak of commandment. To the Christians of his community, he reveals the wonders of the heart of God he contemplated in Jesus. He found that “God is light and there is no darkness in him,” that is why Christians must walk “in the light, as he is in the light” (1 Jn 1:5-7). Then his mystical gaze went beyond and captured the heart of the divine life: God is love. It is from this infinite source that love emanates and spreads among people.

One does not love for an imposition, but for an inner need, for the impulse that comes from the new heart, from the heart of the children of the One who “is love.” Love for the Christian is a given fact; is the necessary manifestation of this new reality in his heart: the divine seed placed in him.

Children of God are those from whose life love emerges. “Those who work for peace, they shall be called children of God” (Mt 5:9); those who love their enemies and pray for their persecutors are “children of your Father in heaven. For he makes his sun rise on both the wicked and the good” (Mt 5:45).

This is a similarity from which even the greatest saint will remain infinitely distant, but towards which we must constantly strive to. In fact, Paul exhorts: “As most beloved children of God, strive to imitate him” (Eph 5:1). Only in Jesus, the only Son of God, the love of the Father’s heart is fully manifested.

The second part of the passage (vv. 9-10) describes what consists love. God has shown his love by giving us what was most precious to him, his Only Begotten Son. He sent him into the world as a “victim of expiation for our sins.” He loved us, not because we were good, but he has made us good by sending his son to involve us in his love, “the time that Christ died for us: when we were still helpless and unable to do anything” (Rom 5:6).

In the last part of the reading (vv. 11-16), John explains what happens in the life of a person when the Spirit, that animates the heart of the Father who is in heaven, is present. The divine sonship is not a reward reserved for those who behave well; it is a free gift. However, it is easy to see where and by whom this divine seed was welcomed: everywhere one notices a spark of love revealing the presence of the divine life; it is there the Spirit of our heavenly Father is acting.

Gospel: Matthew 11:25-30

God’s heart will never cease to amaze, reserving surprises in store even if not everyone will be able to seize them. In today’s Gospel, Jesus suggests the interior dispositions necessary to be able to understand the gestures of the love of the Father and to be involved in it.

At the beginning of his public life, along the Sea of Galilee, Jesus has stirred many enthusiasts and had considerable success. Full of wonder at the miracles worked by him, the crowds were asking: “Who can this be?” (Mk 4:41), “How did this come to him? What kind of wisdom has been given to him?” (Mk 6:2).

But soon misunderstandings began: people began to struggle to understand and respond to the new message he preached. The Pharisees, inflexible guardians of the law, almost immediately opposed him as perverting the sacred traditions of their people. Even many disciples, puzzled by his proposals, separated themselves and turned away from him (Jn 6:66). Even his family has shown themselves quite cold and distrustful: “For neither did his brothers believe in him”—says John (Jn 7:5).

Only a small group of disciples belonging to the poorer classes and despised by the Jewish society remained with Jesus. The Master is not agitated and to the Twelve—confused and bewildered by his discourse on the bread of life—he asked a provocative question: “Will you also go away.” On behalf of all, Peter could only reply: “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (Jn 6:67-69). There is nothing to wonder about this general confusion: it is not easy for anyone to understand the heart of God who revealed himself in Christ.

This passage must be placed in this difficult time of Jesus’ preaching. Chapter 11 of Matthew’s Gospel from which it is taken, begins by introducing the crisis of faith of the Baptist. He sends some of his disciples to ask Jesus: “Are you the one who is to come or should we expect someone else?” (Mt 11:3), then the passage continues with the heavy judgment of Jesus on his generation (Mt 11:16-19) and with the threat: “Alas for you Chorazin and Bethsaida” (Mt 11:21-24).

In the middle of public life, the balance could only be seen as disappointing. Faced with a similar failure, we would have dropped our arms. Jesus instead rejoices for what happened and says: “Father, Lord of heaven and earth, I praise you because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to simple people” (v. 25).

The wise and the intelligent are often mentioned together in the Bible and, many times, in a pejorative sense. They are those who declare themselves devoted researchers of wisdom. They even think of having the monopoly, while in reality, they rack their brains in foolishness and revel in vain disquisition. Against them, the prophet Isaiah had declared: “Woe to those who are wise in their own eyes and take themselves for sages” (Is 5:21).

Jesus does not declare them excluded from salvation. He merely states a fact: the poor, the humble, marginalized people were first to welcome his liberating word. It is normal—he says—that this happens because the small ones, more than any other, feel the need of God’s tenderness, hunger, and thirst for justice, weep, live in grief, and wait for the Lord to intervene to lift their head and fill them with joy. They are blessed because for them the kingdom of God has come. Then he adds: this fact is part of the Father’s plan: “Yes, Father, this is what pleased you” (v. 26).

The belief that God is a friend only of the good and the righteous, who prefers those who behave well and bears with difficulty those who sin, is deeply rooted. This is the God created by the “wise” and the “intelligent.” It is the product of human logic and criteria.

The Father of Jesus instead goes to recover those that we throw in the trash. He prefers those who are despised and those who are not paid attention to by anyone, the public sinners (Mt 11:19) and prostitutes (Mt 21:31) because they are the most in need of his love.

The rich, the satiated, those who are proud of their knowledge do not need this Father. They hold tight to their God. They will also reach salvation, of course, but only when they make themselves “small ones.” The trouble for them is that of arriving late, of losing precious time.

In the second part of the passage (v. 27), an important statement of Jesus is introduced: “No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.”

The verb ‘to know’ in the Bible does not mean having met or contacted a person a few times. It means ‘to have had a profound experience of the person.’ It is used, for example, to indicate the intimate relationship that exists between husband and wife (cf. Lk 1:34).

A full knowledge of the Father is possible only to the Son. However, he may communicate this experience to anyone he wants. Who will have the right disposition to accept his revelation? The small ones, of course.

The scribes, rabbis, those who are educated in every detail of the law, are convinced that they have the full knowledge of God. They maintain they know how to discern what is good. They present themselves as guides for the blind, as light to those who are in darkness, as educators of the ignorant, as masters of the simple ones (Rom 2:18-20). As long as they do not give up their attitude of being “wise” and “intelligent” people, they preclude the true and rewarding experience of God’s love.

The last part of the passage (vv. 28-30) refers to the oppression that the “small ones,” the simple people of the land, the poor, those who suffer from the “wise and intelligent.”

They (the scribes and Pharisees) have structured a very complicated religion, made up of minute rules, prescriptions impossible to observe. They loaded the shoulders of ignorant people “unbearable burdens … that they do not even move a finger to help them” (Lk 11:46).

The law of God, yes, is a yoke and the wise Sirach recommended to his son: “Put her constraints on your feet and her yoke on your neck … do not rebel against the chains … you will find in her your rest” (Sir 6:24-28), but the religion preached by the masters of Israel has transformed it into an oppressive yoke. For this, the poor not only feel wretched in this world but also rejected by God and excluded from the world to come.

The poor, unable to observe the provisions dictated by the rabbis, are convinced that they are impure: “Only this cursed people who have no knowledge of the law” declared the high priest Caiaphas (Jn 7:49). To these poor, lost and disoriented people, Jesus addressed the invitation to be free from fear and distressing religion instilled in them. He recommends: Accept my law, the new one that is summed up in a single commandment: love because in God’s heart there is only love.

He does not propose an easier and permissive moral, but an ethic that points directly to the essential. It does not make one waste energies in the observance of prescriptions “that has the appearance of wisdom” but in reality, they have no value (Col 2:23).

His yoke is sweet. First of all, because it is his: not in the sense that he imposed it, but because he carried it first. Jesus always bent down to the Father’s will. He freely embraced it while he never imposed human precepts (Mk 7). His yoke is sweet because only those who accept the wisdom of the beatitudes can experience the true joy.

Finally, the invitation: “Learn from me for I am meek and humble of heart” (v. 29). Perhaps this statement leaves us a bit confused because it seems a deserved auto-celebration, certainly, but not appropriate. These words are nothing more than a boast. “Learn from me” simply means: do not follow the teachers who act as masters on your consciences. They preach a God who is not on the side of the poor, the sinners and the last. They teach a religion that takes away the joy with its fussiness and absurdity.

Jesus presents himself as meek and humble of heart. These are the terms that we find in the Beatitudes. They do not indicate the timid, the meek, the quiet, but those who are poor and oppressed and those who, while suffering injustice, do not resort to violence.

Jesus experienced dramatic conflicts, but he confronted them with the disposition of heart that characterizes the “meek.” He did not renounce to confront the forces of evil; he did not escape far away from the world and from the problems of people. He has a meek heart because he made himself small; he chose the last place, and put himself at the service of people and assumed the attitude of a slave.

This is the “yoke” that he proposes also to his disciples. To all these poor people of the land, Jesus says: I’m on your side, I am one of you; I am poor and rejected.

This Gospel passage invites us to make both personal and community reflection. Which God do we believe in? Is he that one of the “wise,” or that one revealed to us by Jesus? For whom is our community a sign of hope, for whom is one convinced of meriting the first place, for whom does one feel unworthy to cross the threshold of the church? Does it testify the tenderness of God’s heart or the stiffness of the legalists’ heart?

Fernando Armellini

https://sundaycommentaries.wordpress.com